See a Bloom, Give it Room! Celebrating Lake Month with EPA’s Harmful Algal Blooms Research

Published July 23, 2024

Many Americans love to spend July by the water at beaches and on lakeshores. Some lakes and reservoirs allow for recreational activities such as boating, fishing, and swimming, but these waterbodies play other vital roles. They can provide drinking water or irrigation water for nearby agricultural fields and can also be a source of hydropower generation for electricity. Lakes serve the important function of capturing rainfall and runoff from land which can help to mitigate floods. Lakes also provide habitat for dynamic ecosystems and a wide range fish and wildlife.

Lakes can have a very significant threat: harmful algal blooms. Most species of algae are not harmful, but sometimes certain types of algae bloom in excessive amounts and can cause harm to health. These blooms are referred to as harmful algal blooms (HABs) and they include both algae and cyanobacteria. Cyanobacteria, also known as blue-green algae, are frequently found in freshwater, estuarine, and marine waters. These tiny, or microscopic, organisms use direct sunlight to produce their own food (i.e., are photosynthetic) and are very important to aquatic ecosystems as many species can fix nitrogen from the atmosphere and make it available to the aquatic food web. However, some of these bacteria can produce cyanotoxins that can create harmful algal blooms.

HABs result from complex ecological processes that are affected by a variety of factors including nutrient and light availability, water temperature, weather patterns, and competition with other organisms. With climate change and land use changes, HABs have the potential to increase in frequency, intensity, and geographic scale. Potential impacts from exposure to HABs and associated toxins include health risks to humans, pets, livestock, wildlife, and other biota; restricted recreational activities; damaged ecological systems; increased water treatment costs; and decreased economic revenue.

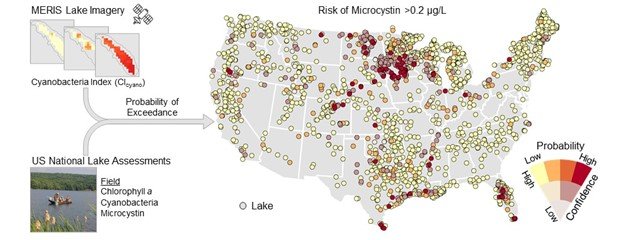

EPA researchers are looking for ways to reduce the negative effects of HABs on human and environmental health and the economy through research on causes, monitoring, mitigation, and treatment of HABs and the assessment of adverse health outcomes from exposure to HABs. One way to reduce these effects is to identify lakes that have a high risk of these blooms. This capability enables water managers to prioritize more time- and resource-intensive field monitoring for these lakes. EPA researchers like Amalia Handler are working on ways to help managers set priorities for lake water monitoring. They combine EPA’s satellite-based Cyanobacteria Assessment Network (CyAN) and field-based National Aquatic Resource Surveys to model rich information about HABs. The satellites provide large-scale surveillance datasets while the survey data offers more detailed information about blooms such as concentrations of the two most common algal toxins. By combining the two datasets, it is possible to estimate the risk of toxic blooms among the satellite-monitored lakes.

“This is an exciting analysis because the satellites cannot determine if a bloom is toxic based only on imagery. Only by combining the satellite and field data can we estimate the risk of toxic blooms among lakes,” Handler said about the process.

By combining the power of two specialized data sources, EPA aims to help local managers set monitoring priorities for their local waterbodies. Water quality managers will be able to prioritize which lakes require additional resource-intensive field monitoring. They will be able to identify near-lake communities that may need targeted education about potential risks of HABs in drinking and recreational waters. Finally, managers will be able to evaluate for vulnerabilities in drinking water infrastructure that are downstream or rely directly on high-risk lakes.

Learn More about the Science