Tiny Plastics, Big Threat: How are Microplastics Impacting our Coral Reefs?

Published November 30, 2021

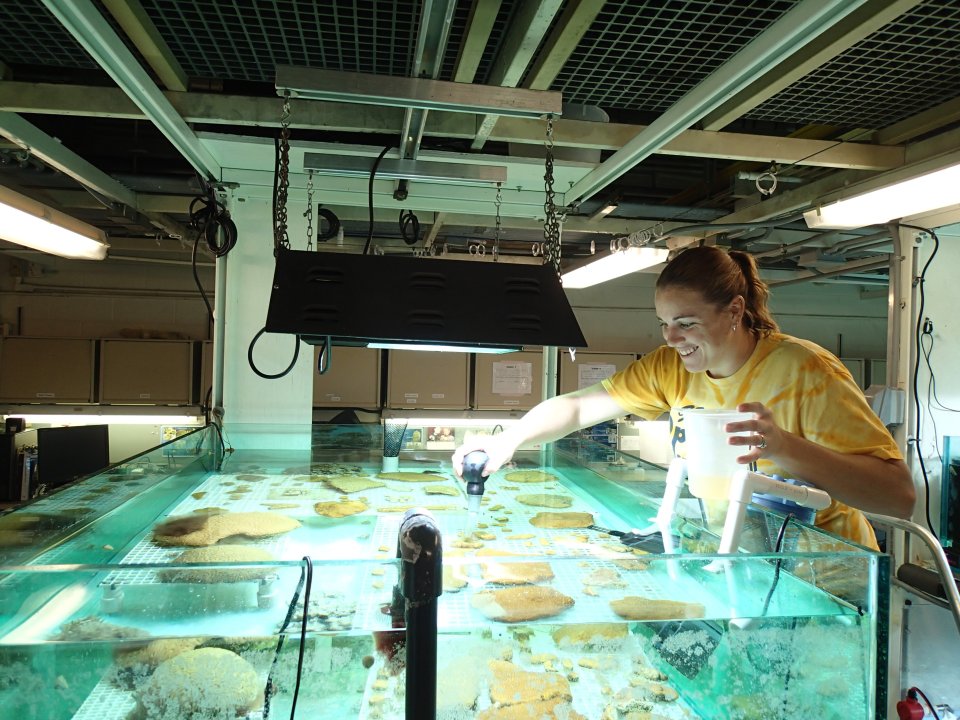

Coral reefs worldwide are under threat from natural and human-made stressors including dredging, climate change, and plastic pollution. At EPA’s Coral Research Facility – an indoor wet lab in Gulf Breeze, Florida – scientists are studying how stressors like sedimentation, ocean acidification, and microplastics are impacting corals’ health.

The facility is EPA’s only corals laboratory and is one of only a few research facilities in the U.S. that operates with recirculating systems. This unique setup uses natural seawater from the Gulf and allows scientists to maintain and grow corals in culture systems for use in research at any point during the corals’ development.

“The advantage of using recirculating systems allows for precise control of all environmental parameters which allows us to focus on effects only from the stressor or stressors in question,” says EPA Coral Biologist, Cheryl Hankins. “This is extremely important so that we can target areas for better management practices.”

Using recirculating systems, researchers can precisely control many environmental factors including temperature, salinity (concentration of salt in the water), light, and other variations in water quality, allowing them to isolate the specific stressors they are studying.

Munching on Microplastics

Recently, EPA scientists studied how microplastics impact two different species of coral and found that long-term exposure to microplastics impaired the corals’ growth. Specialized lab equipment at the facility allows researchers to estimate corals’ 3-D surface areas using 2-D photogrammetry. Unlike other measurement methods that can destroy coral samples, photogrammetry is non-destructive and allows researchers to measure the growth rate of corals without harming them throughout experiments.

“What is still unknown are the exact mechanisms that are causing adverse effects,” Hankins explains. “Ingested microplastics could block the corals’ digestive tracts, which would either leave them feeling satiated, like they have a full stomach, or prevent digestion of their natural diet.”

Additional research has shown that microplastics adhering to coral tissue could also be impacting coral, either by preventing them from capturing prey or causing them to lose precious energy removing microplastics from their surface.

Although scientists now know that microplastics can impact coral, the next steps will be to determine if other stressors, such as increased temperature, combined with microplastics have cumulative impacts on coral. While EPA’s Coral Research Facility has focused primarily on Atlantic corals, scientists are exploring options to study Pacific corals in the future.

Hankins looks forward to investigating the stressors that plague coral reefs, knowing that her research will have direct impacts on how reef habitats are managed. “Coral reefs are valuable for their economic, ecological, and cultural benefits,” she says. “Not to mention, coral reefs cover less than 1% of the Earth’s surface but house 25% of the world’s biodiversity – it would be a shame to lose all that flora and fauna.”