The Guardian: Origins of the EPA

EPA Historical Publication-1

Spring 1992

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Predecessor: Conservation

- From Ecology To Environmentalism

- An Environmental Revolution

- An Agency For The Environment

- The First Administrator

Introduction

American environmentalism dawned as a popular movement on a mild spring afternoon in 1970. Wednesday, April 22nd, brought blue skies, light breezes, and temperatures in the 60s to New York City and Washington, D.C. Much of the rest of the country enjoyed similar conditions. On that day, the influence of nature had particular meaning; the nation held a celebration of clean air, land, and water. Encouraged by the retreat of winter, millions participated.

The first Earth Day may have been prompted, in part, by the recent moon landings. When the astronauts turned their cameras homeward, capturing the image of a delicate blue planet, the world looked upon itself with fresh understanding. The context of Earth Day 1970, however, was far from celestial, reflecting the turbulence of the time. Since the mid-1960s, the streets has become a common outlet for political and social discontent. Yet Earth Day, forged in an era of strife and change, had its own personality; marijuana smoke may have hung in wisps over some of the day's festivities, but violence and confrontation were nowhere to be seen.

In America's largest city, Mayor John V. Lindsey decided to commemorate the day in high style, closing traffic for two hours on Fifth Avenue, from 14th Street to Central Park. Along its broad path, multitudes choked the streets and sidewalks. Much of the crowd's interest centered on Union Square, a crossroads of political ferment during the 1930s. This day, "many more than" 100,000 onlookers saw teach-ins, lectures, and a non-stop frisbee game at the famous intersection. An ecological Mardi Gras lasting from noon to midnight sprang up along 14th Street from Third to Seventh Avenues. While folksinger Odetta sang "We Shall Overcome," a rock band played the Beatles' anthem, "Power to the People." In Washington, D.C., Congress suspended business as most of its members, regardless of ideology, felt compelled to appear before their constituents. President Nixon kept a regular schedule at the White House.

Predecessor: Conservation

While Earth Day launched the idea of environmentalism in its present sense, the realization of the value of wilderness and an appreciation of the consequences of its destruction dates back several centuries in America. For example, as early as 1652, the city of Boston established a public water supply, a step followed in the next century by several towns in Pennsylvania. By 1800, 17 municipalities had taken similar measures to protect their citizens against unfit drinking sources. Still, anyone living in the great cities of New York, Philadelphia, Charleston, and Boston just after the American revolution could not escape the ill-effects of expanding urbanization: the stench of sewage in near-by rivers; the unwholesome presence of animal and human wastes underfoot; the odors of rotting food; the jangling shouts of vendors in narrow lanes; and the constant grinding of hooves and iron wagon wheels on unpaved streets.

Industrialism in the nineteenth century widened the impact of environmental degradation. Literary people were the first to sense the meaning of this trend. Herman Melville's epic novel Moby Dick (1851) and Henry David Thoreau's Walden, or Life in the Woods (1854) emphasized, respectively, the power and the tranquility of nature. A second generation of writers, perhaps sobered by the final settlement of the American West, wrote without fictional guise. John Burroughs published 27 volumes of intimate, experiential nature essays. John Muir, the Scottish prophet of the rugged outdoors, set down his observations in a series of books, beginning with The Mountains of California in 1894.

President Theodore Roosevelt, who undertook a western camping trip with Muir in 1903, came to symbolize the campaign for conservation, which gained steadily in political popularity. During and after his Administration, the use and retention of natural resources became a preoccupation of government.

President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal enacted a number of natural resource measures. The Soil Conservation Service, founded in 1935, applied scientific practices to reduce the erosion of agricultural land. The depletion of animal life received recognition in the passage of the 1937 Pittman-Robertson Act, establishing a fund for state fish and wildlife programs from the proceeds of federal taxes on hunting and fishing equipment. Most ambitious of all, the Tennessee Valley Authority erected nine dams and a string of massive generating stations.

From Ecology To Environmentalism

The definition of wilderness as an immense natural storehouse, subject to human management, changed after the Second World War. Life on the battle front, as well as the home front, curbed the country's appetite for colossal federal projects. Moreover, the almost immediate demobilization of the armed forces in 1945 and 1946 resulted in an unprecedented national birthrate. Cheap home loans for veterans pushed suburban settlement far beyond the city skylines. As the middle class found itself living on the edges of open lands, political questions surfaced about the preservation of the landscape just over the back fence. The concept of ecology--which valued esthetics and biology over efficiency and commerce--began to penetrate the public mind.

The growth of the cities also made plain the evils of pollution. Media stories covered radioactive fallout and its effect on the food chain, dangerous impurities in urban water supplies, and the deterioration of city air. The subtle metaphor of a "web of life," in which all creatures depended upon one another for their mutual perpetuation, gained common currency. Hence, the powerful reaction to Rachel Carson's 1962 classic Silent Spring, a quietly shocking tale about the widespread pesticide poisoning of man and nature. Her book elicited a public outcry for direct government action to protect the wild; not for its future exploitation, but for its own innate value.

In the process of transforming ecology from dispassionate science to activist creed, Carson unwittingly launched the modern idea of environmentalism: a political movement which demanded the state not only preserve the Earth, but act to regulate and punish those who polluted it. Sensing the electoral advantage from such advocacy, Presidents Kennedy and Johnson added the environment to their speeches and legislative programs. In his 1964 and 1965 messages to Congress, Lyndon Johnson spoke forcefully about safeguarding wilderness and repairing damaged environments.

Richard Nixon showed as much eagerness as his predecessors to profit from the issue, and he invoked it during the bitter presidential election of 1968. As President, however, he acted with ambivalence, moving in two directions at once. On one hand, he raised eyebrows by appointing a National Pollution Control Council, a Commerce Department body comprised solely of corporate executives. He also vetoed the second Clean Water Act. At the same time, in 1969 and 1970, he approved and directed a succession of sweeping measures which vastly expanded the federal regulatory protections afforded the environment.

An Environmental Revolution

Just four months after his January 1969 inauguration, President Nixon established in his cabinet the Environmental Quality Council, as well as a complementary Citizens' Advisory Committee on Environmental QuaIity. Opponents denounced both as ceremonial and Nixon, ever sensitive to criticism, rose to the challenge. He had already asked Roy L. Ash, the founder of Litton Industries, to lead an Advisory Council on Executive Organization and submit recommendations for structural reform. In November, the President's Domestic Council instructed Ash to study whether all federal environmental activities should be unified in one agency. During meetings in spring 1970, Ash at first expressed a preference for a single department to oversee both environmental and natural resource management. But by April he had changed his mind; in a memorandum to the President he advocated a separate regulatory agency devoted solely to the pursuit of anti-pollution programs.

Forging such an institution actually represented the final step in a quick march towards national environmental consciousness. Congress recognized the potency of the issue in late 1969 by passing the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). This statute recast the government's role: formerly the conservator of wilderness, it now became the protector of earth, air, land, and water. The law declared Congressional intent to "create and maintain conditions under which man and nature can exist in productive harmony," and to "assure for all Americans safe, healthful, productive, esthetically and culturally pleasing surroundings." Henceforth, all federal agencies planning projects bearing on the environment were compelled to submit reports accounting for the likely consequences--the now famous Environmental Impact Statements (EISs).

Secondly, NEPA directed the President to assemble in his Cabinet a Council on Environmental Quality. Undersecretary of the Interior Russell E. Train agreed to be its first chairman. The Council's three members and staff would assist the President by preparing an annual Environmental Quality Report to Congress, gathering data, and advising on policy. Signing the Act with fanfare on New Year's Day 1970, Nixon observed that he had "become further convinced that the 1970s absolutely must be the years when America pays its debt to the past by reclaiming the purity of its air, its waters, and our living environment. It is," he said, "literally now or never."

Pressing the initiative in his State of the Union Address three weeks later, the President proclaimed the new decade a period of environmental transformation. On February 10, he presented the House and Senate an unprecedented 37-point message on the environment, requesting four billion dollars for the improvement of water treatment facilities; asking for national air quality standards and stringent guidelines to lower motor vehicle emissions; and launching federally-funded research to reduce automobile pollution. Nixon also ordered a clean-up of federal facilities which had fouled air and water, sought legislation to end the dumping of wastes into the Great Lakes, proposed a tax on lead additives in gasoline, forwarded to Congress a plan to tighten safeguards on the seaborne transportation of oil, and approved a National Contingency Plan for the treatment of petroleum spills.

An Agency For The Environment

Having dispatched these initiatives in spring, by early July the Administration could concentrate its full attention on the capstone of its program. Acting on Roy Ash's advice, the President decided to establish an autonomous regulatory body to oversee the enforcement of environmental policy. In a message to the House and Senate, he declared his intention to establish the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and left no doubts about its far-reaching powers. Nixon declared that its mission would center on:

- The establishment and enforcement of environmental protection standards consistent with national environmental goals.

- The conduct of research on the adverse effects of pollution and on methods and equipment for controlling it; the gathering of information on pollution; and the use of this information in strengthening environmental protection programs and recommending policy changes.

- Assisting others, through grants, technical assistance and other means, in arresting pollution of the environment.

- Assisting the Council on Environmental Quality in developing and recommending to the President new policies for the protection of the environment.

The President accompanied his statement with Reorganization Plan Number 3, dated July 9, 1970, in which he informed Congress of his wish to assemble the EPA from the sinews of three federal Departments, three Bureaus, three Administrations, two Councils, one Commission, one Service, and many diverse offices. The Interior Department would yield the Federal Water Quality Administration, as well as all of its pesticides work. The Department of Health, Education, and Welfare would contribute the National Air Pollution Control Administration, the Food and Drug Administration's pesticides research, and the Bureaus of Solid Waste Management, Water Hygiene, and (portions of) the Bureau of Radiological Health. The Agriculture Department would cede the pesticides activities undertaken by the Agricultural Research Service, while the Atomic Energy Commission and the Federal Radiation Council would vest radiation criteria and standards in the proposed agency. Finally, the Council on Environmental Quality's ecological research would be transferred to EPA.

The hearings on EPA, held in summer 1970, essentially supported the President. The House Government Operations Subcommittee on Executive and Legislative Reorganization, chaired by Congressman Chet Holifield of California, convened on July 22, 23, and August 4, to take testimony on Reorganization Plan Number 3. Lead witness Russell Train gave it unqualified support, predicting that its "vision of clean air and water...will provide us with the unity and the leadership necessary to protect the environment." Roy Ash testified the following day about the fragmented state of pollution control, the continuation of which "will seriously limit our solving the problem even as we expand our commitment to preserve and restore the quality of our environment."

Meanwhile, witnesses appeared on July 28 and 29 before the Senate Government Operations Subcommittee on Executive Reorganization and Government Research, chaired by Senator Abraham Ribicoff of Connecticut. During these hearings, Senator Jacob Javits of New York perhaps expressed the prevailing mood of the Congress when he described the new organization as a "very strong and overdue effort to arrest and prevent the erosion of the priceless resources of all mankind and also to preserve that most priceless asset, the human being himself, who, in a singularly polluted atmosphere, may find it impossible to exist."

Congressman John Dingell of Michigan presented the only serious alternatives to Reorganization Plan Number 3. A strongwilled conservationist, Dingell wondered why the EPA encompassed neither water and sewer programs in the Departments of Agriculture and Housing and Urban Development, nor the environmental operations of the Defense and Transportation Departments. He proposed that instead of erecting EPA, the House consider a more comprehensive, cabinet-level Department of Environmental Quality. Despite his suggestion, both subcommittees approved the President's proposal and issued reports: the Holifield Committee on September 23, the Ribicoff panel six days later. Having cleared all its statutory hurdles, on December 2, 1970, the Environmental Protection Agency would at last open its doors.

The First Administrator

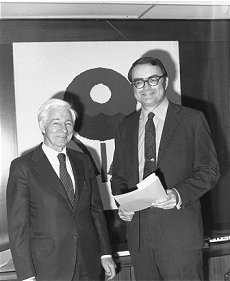

While the EPA plan underwent Congressional scrutiny, practical preparations proceeded at the Office of Management and Budget. A nine-man Task Force on EPA Organization met through summer and fall 1970 to design the structure of the new institution. By early October, the participating government Departments informed their employees of the transfer of functions and personnel entailed in establishing the new agency. Finally, on November 6, 1970, President Nixon announced his intention to nominate William D. Ruckelshaus to be the first Administrator.

A graduate of Princeton University and Harvard Law School, the 38-year-old Indianan had already compiled an impressive record of government service. At the age of 28 he was appointed a Deputy State Attorney General and in that capacity drafted the Indiana Air Pollution Control Act of 1963. In 1967, Ruckelshaus sought elective office and not only won a Republican seat in the state House of Representatives, but also became the first person to be named Majority Leader during his initial term. A rising political star, he was nominated to run for the U.S. Senate, but lost in the general election. At the time of his selection to head EPA, Ruckelshaus was serving in the Department of Justice as Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Division.

During his confirmation hearings on December 1 and 2, Ruckelshaus received a warm reception from the Senate Committee on Public Works. His first words to the Senators not only laid the basis for his term as Administrator, but for the future of the Agency itself.

"I think that enforcement is a very important function of this new Agency. Obviously, if we are to make progress in pollution abatement, we must have a firm enforcement policy at the federal level. That does not mean that this policy will be unfair, that it will not be evenhanded, but it does mean that it will be firm.... [A]s far as I view the mission of this Agency and my mission as its proposed Administrator, it is to be as forceful as the laws that Congress has provided, and to present...firm support [for] enforcement [by] the States."

After taking the Oath of Office on December 4, 1970 the Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency officially welcomed his staff, transferred just two days before from their former agencies and departments. William Ruckelshaus appealed to their zeal and sense of mission as they joined the newest independent federal agency, asking them to "keep moving ahead with the valuable work which is already underway [and] give us your ideas, your hard work and support in building a new and effective organization."

Photo Credits:

Cover, NASA, Apollo 16 Earth-Moon round trip

All others, EPA Historical photographs

designed by Ron Farrah, EPA

Corrections: This publication incorrectly spelled John V. Lindsay's name. It also incorrectly attributed "Power To The People," a solo recording by John Lennon, to the Beatles.