The Mississippi/Atchafalaya River Basin (MARB)

History

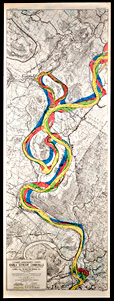

The Mississippi River originates as a tiny outlet stream from Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota. During a meandering 2,350 mile journey south to the Gulf of America, the Mississippi River is joined by hundreds of tributaries, including the Ohio and Missouri Rivers. Water from parts or all of 31 states drains into the Mississippi River, and creates a drainage basin over 1,245,000 square miles in size. Before reaching the Gulf, the Mississippi meets up with its distributary, the Atchafalaya River.

The Mississippi/Atchafalaya River Basin (MARB), which encompasses both the Mississippi and the Atchafalaya River Basins, is the third largest in the world, after the Amazon and Congo basins. Parts or all of 31 states plus two Canadian provinces drain into the Mississippi River, totaling 41% of the contiguous United States and 15% of North America. Along with being the largest U.S. drainage basin, the Mississippi also creates borders for 10 states. The Mississippi River provides necessary resources to the United States and the world and has helped to shape American history and commerce, including tourism and the fishing industry. According to U.S. Census data, nearly 30% of Americans live in the MARB.

Prior to the Louisiana Purchase, the Mississippi River acted as the western border for the United States. The water way was first used for trade with Indian tribes when fur pelts were floated down the river from Ohio. Once steamboats were invented, the Mississippi River became an important mode of transportation that revolutionized river commerce. Manmade locks and dams were created to control flooding and create deeper waters for steamboats. However, this system made it more difficult for water to be absorbed and made flooding even more detrimental. The convenience of a trustworthy mode of transportation and a constant water supply encouraged agriculture, industries, and cities to spread to areas along the river. Productivity from these areas resulted in large amounts of nutrients being discharged from the river system into the Gulf of America. These nutrients have contributed to hypoxia.

The natural capacity of the MARB to remove nutrients has been diminished by a range of human activities. The Mississippi is one of the most heavily engineered rivers in the United States. Over time, the character of the old river meanders and floodplains have been modified for millions of acres of agriculture and urbanization. Many of the original freshwater wetlands, riparian zones and adjacent streams and tributaries along the Mississippi have been disconnected from the river by levees and other engineering modifications. This has caused a loss of habitat for native plants and animals and has reduced the biological productivity of the entire river basin. Historically, the coastal marshes of Louisiana have provided a natural barrier against the erosion caused by the fierce storms which often come from the Gulf by neutralizing some of the flow energy of the water. This capacity has been reduced by channelization.

Over the years, traffic on the river has caused increased bank erosion, turbidity, sediment resuspension, and disruption of native species habitats. The increased amount of river dredging, levee building, and construction that comes along with this traffic impairs aquatic life in many ways by disturbing their habitat.