Health Effects of Ozone in the General Population

- Introduction

- How are people exposed to ozone?

- How does ozone react in the respiratory tract?

- What are ozone's acute physiological and symptom effects?

- What effects does ozone have at the cellular level?

- How does response vary among individuals?

- What are the effects of ozone on mortality?

- What are other potential effects of short-term ozone exposure?

- At what exposure levels are effects observed?

- What are the effects of recurrent or long-term exposure to ozone?

Introduction

Breathing ground-level ozone can result in a number of health effects that are observed in broad segments of the population. Some of these effects include:

- Induction of respiratory symptoms

- Decrements in lung function

- Inflammation of airways

Respiratory symptoms can include:

- Coughing

- Throat irritation

- Pain, burning, or discomfort in the chest when taking a deep breath

- Chest tightness, wheezing, or shortness of breath

In addition to these effects, evidence from observational studies strongly indicates that higher daily ozone concentrations are associated with increased asthma attacks, increased hospital admissions, increased daily mortality, and other markers of morbidity. The consistency and coherence of the evidence for effects upon asthmatics suggests that ozone can make asthma symptoms worse and can increase sensitivity to asthma triggers.

Figure 2: Pyramid of effects caused by ozone

The relationship between the severity of the effect and the proportion of the population experiencing the effect can be presented as a pyramid. Many individuals experience the least serious, most common effects shown at the bottom of the pyramid. Fewer individuals experience the more severe effects such as hospitalization or death.

How are people exposed to ozone?

Primary exposure occurs when people breathe ambient air containing ozone. The rate of exposure for a given individual is related to the concentration of ozone in the surrounding air and the amount of air the individual is breathing per minute (minute ventilation). The cumulative amount of exposure is a function of both the rate and duration of exposure.

Although ozone concentrations in the outside (ambient) air are generally similar across many locations in a particular airshed, a number of factors can affect ozone concentration in "microenvironments" within the larger airshed (e.g., inside a residence, inside a vehicle, along a roadway). Ozone concentrations indoors typically vary between 20% and 80% of outdoor levels depending upon whether windows are open or closed, air conditioning is used, or other factors such as indoor sources. People with the greatest cumulative exposure are those heavily exercising outdoors for long periods of time when ozone concentrations are high. In addition, during exercise people breathe more deeply, and ozone uptake may shift from the upper airways to deeper areas of the respiratory tract, increasing the possibility of adverse health effects. People with the lowest cumulative exposure are those resting for most of the day in an air-conditioned building with little air turnover.

Ozone levels may also affect indoor levels of some aldehydes formed as reaction products of ozone with indoor substances (Apte et al 2008). This provides a potential pathway for people indoors to experience respiratory effects mediated by ozone reaction products. Further research is needed to test the importance of these exposures on health effects.

How does ozone react in the respiratory tract?

Because ozone has limited solubility in water, the upper respiratory tract is not as effective in scrubbing ozone from inhaled air as it is for more water soluble pollutants such as sulfur dioxide (SO2) or chlorine gas (Cl2). Consequently, the majority of inhaled ozone reaches the lower respiratory tract and dissolves in the thin layer of epithelial lining fluid (ELF) throughout the conducting airways of the lung.

In the lungs, ozone reacts rapidly with a number of biomolecules, particularly those containing thiol or amine groups or unsaturated carbon-carbon bonds. These reactions and their products are poorly characterized, but it is thought that the ultimate effects of ozone exposure are mediated by free radicals and other oxidant species in the ELF that then react with underlying epithelial cells, with immune cells, and with neural receptors in the airway wall. In some cases, ozone itself may react directly with these structures. Several effects with distinct mechanisms occur simultaneously following a short-term ozone exposure and will be described below.

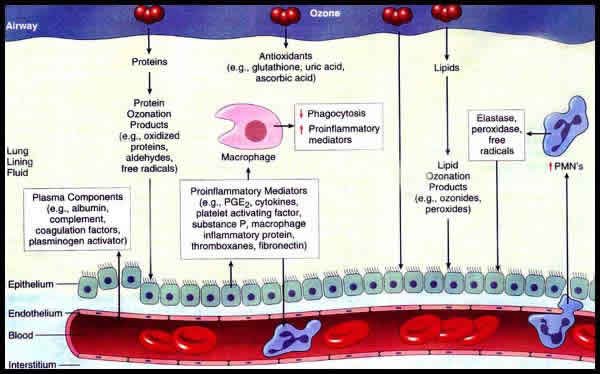

Figure 3: Ozone is highly reactive in the respiratory tract

When breathed into the airways, ozone interacts with proteins and lipids on the surface of cells or present in the lung lining fluid, which decreases in depth from 10 µm in the large airways to 0.2 µm in the alveolar region. Epithelial cells lining the respiratory tract are the main target of ozone and its products. These cells become injured and leak intracellular enzymes such as lactate dehydrogenase into the airway lumen, as well as plasma components. Epithelial cells also release a variety of inflammatory mediators that can attract polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) into the lung, activate alveolar macrophages, and initiate a train of events leading to lung inflammation. Antioxidants present in cells and lining fluid may protect the epithelial barrier against damage by ozone or its reaction products.

Source: Devlin et al., (1997)

What are ozone's acute physiological and symptom effects?

The predominant physiological effect of short-term ozone exposure is being unable to inhale to total lung capacity. Controlled human exposure studies have demonstrated that short-term exposure - up to 8 hours - causes lung function decrements such as reductions in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), and the following respiratory symptoms:

- Cough

- Throat irritation

- Pain, burning, or discomfort in the chest when taking a deep breath

- Chest tightness, wheezing, or shortness of breath

The effects are reversible, with improvement and recovery to baseline varying from a few hours to 48 hours after an elevated ozone exposure.

Current thinking is that changes in symptoms and lung function are due to stimulation of airway neural receptors (probably airway C-fibers) and transmission to the central nervous system via afferent vagal nerve pathways. Although ozone exposure results in some airway narrowing, neural inhibition of inhalation effort at high lung volumes is believed to be the primary cause of being unable to inhale to total lung capacity.

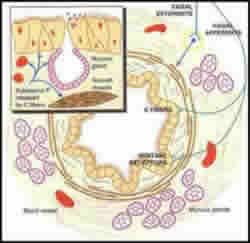

Figure 4: Ozone induces neurally mediated responses in the bronchial airways

Stimulation of nociceptive interepithelial nerve fibers by ozone leads to reflex cough and a decrease in maximal inspiration that is relieved by opioid agonists, which block sensory pathways. Two possible mechanisms are involved: (1) stimulation of irritant receptors contributes to cough and induces a vagally mediated reflex that increases airway resistance, probably via airway smooth muscle contraction that is blocked by atropine; (2) C fiber stimulation releases neurokinins such as substance P that dilate nearby capillaries, activate mucous glands, and contract airway smooth muscle via neurokinin receptors. Prostaglandin E2 released by epithelial cells exposed to ozone or to ozone reaction products also sensitizes C fibers.

Source: Devlin et al. (1997)

The overall effect is thus primarily restrictive in nature with a smaller obstructive component that reflects itself in decreases in forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1 and other spirometric measures that require a full inspiration. It is likely that these lung function changes and respiratory symptoms are responsible for observations that short-term ozone exposure limits maximal exercise capability.

Ozone-induced changes in breathing pattern to more rapid shallow breathing may also be a manifestation of C-fiber stimulation and may be a protective response to limit penetration of ozone deep into the respiratory tract. Such effects may also contribute to changes in deposition pattern and retention of other inhaled substances such as allergens and particle pollution (also called particulate matter).

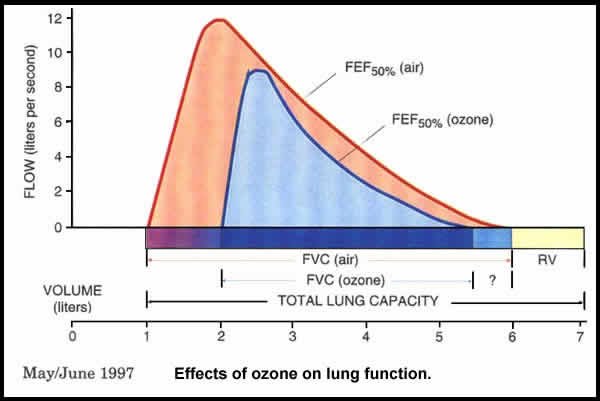

Figure 5: Effects of ozone on lung function

Ozone reduces the maximal inspiratory position (at the left of the curves) and may slightly increase the residual volume (at the right). Reduction in maximum inspiration reduces forced vital capacity (FVC), and this causes a reduction in expiratory flow measurements, such as flow at 50% of FVC expired (FEF50%). Because ozone causes only a small change in resistance, the relationship between flow and volume is not changed to a large extent. Source: Devlin et al. (1997)

What effects does ozone have at the cellular level?

As a result of short-term exposure, ozone and/or its reactive intermediates cause injury to airway epithelial cells followed by a cascade of other effects. These effects can be measured by a technique known as bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), in which samples of epithelial lining fluid (ELF) are collected during bronchoscopy on volunteers experimentally exposed to ozone. Cells and biochemical markers in the lavage fluid and in the blood can be analyzed to provide insight into the effects of exposure.

Evidence for airway inflammation following ozone exposure includes visible redness of the airway seen during bronchoscopy as well as an increase in the numbers of neutrophils in the lavage fluid. Cellular injury is suggested by an increase in the concentration of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), an enzyme released from the cytoplasm of injured epithelial cells, in the ELF. Mediators (e.g., cytokines, prostaglandins, leukotrienes) that are released by injured cells include a number that attract inflammatory cells resulting in a neutrophilic inflammatory response in the airway. In addition, ozone reaction products as well as some mediators produced in the lung can be detected in the blood providing a possible mechanism for extrapulmonary effects of ozone exposure.

Figure 6: Effects of ozone on lung function

These photos show a healthy lung airway (left) and an inflamed lung airway (right).Photos courtesy of PENTAX Medical Company.

Other documented ozone-induced effects that may be related to the underlying injury and inflammatory response are:

- An increase in small airway obstruction

- A decrease in the integrity of the airway epithelium

- An increase in nonspecific airway reactivity

- A decrease in phagocytic activity of alveolar macrophages

The decrease in epithelial integrity can be measured by an increase in the concentration of plasma proteins appearing in the ELF following exposure and by more rapid clearance of inhaled radio-labeled markers from the lung to the blood. This has the potential for allowing increased movement of inhaled substances (e.g. allergens or particulate air pollution) from the airway to the interstitium or the blood and could modify the known effects of inhaled allergen on asthma and particulate matter on mortality.

Although the significance of increased nonspecific airway reactivity to substances such as methacholine or histamine is not understood in healthy individuals, it is clearly of concern for people with asthma, as increased airway reactivity is a predictor for asthma exacerbations. (See bulleted section, How does ozone affect people with asthma?).

A decrease in macrophage function has the potential to interfere with host defense. Over a period of several days following a single short-term exposure, inflammation, small airway obstruction, and increased epithelial permeability resolve; damaged ciliated airway epithelial cells are replaced by underlying cells; and damaged type I alveolar epithelial cells are replaced by more ozone-resistant type II cells. Over a period of weeks, the type II cells differentiate into type I cells, and following this single exposure, the airway appears to return to the pre-exposure state.

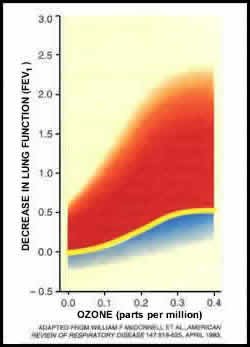

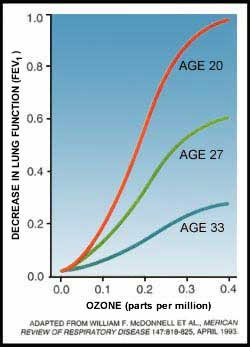

How does response vary among individuals?

One striking characteristic of the acute responses to short-term ozone exposure is the large amount of variability that exists among individuals. For example, for a 2-hour exposure to 400 ppb ozone (note: 400 ppb is equal to .4 ppm) that includes 1 hour of heavy exercise, the least responsive individual may experience no symptom or lung function changes while the most responsive individual may experience a 50% decrement in FEV1 and have severe coughing, shortness of breath, or pain on deep inspiration. A similar range of response is evident for a 6.6-hour exposure to 80 ppb with 5 hours of moderate activity. Other individual responses fall into what appears to be a unimodal distribution between these two extremes. Those with large responses following exposure on one day also tend to have large responses upon re-exposure. Similarly, those with small responses following exposure on one day tend to have small responses upon re-exposure. A small fraction of the observed variability in lung function and symptom responsiveness can be explained by differences in age and in body mass index (BMI) with young adults (teens to thirties) and those with high BMI being much more responsive than older adults (fifties to eighties) and those with low BMI. Results similar to those in Figure 8 are also seen with longer duration exposures to concentrations more relevant to ambient levels (e.g. over a range of 60 to 120 ppb).

Source: Devlin et al. (1997) |

Source: Devlin et al. (1997) |

Individual differences in the intensity of the inflammatory response also exist, and it appears that these differences in response are also stable over time. The magnitude of the neurally-mediated lung function response, however, is not related to the degree of cell injury and inflammation for a given individual suggesting that these two effects are the result of different mechanisms of action. Further evidence for multiple mechanisms of action is provided by drug intervention studies. There is some evidence that Vitamin C and E supplements may slightly reduce the lung function effects of ozone but not the inflammatory or symptom responses. Pre-treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) reduces lung function and symptom responses but not the inflammatory responses in non-asthmatics. In asthmatic volunteers NSAID pretreatment did not block the restrictive lung function changes seen in nonasthmatics, but did blunt some of the changes due to airway obstruction. Pre-treatment with high doses of inhaled steroids has been shown to reduce the neutrophil influx following ozone exposure in people with asthma, but not in those without asthma.

True differences in individual responsiveness to ozone can be the result of either environmental or genetic factors. Research has demonstrated that genetic differences among strains of mice can explain the large range of inflammatory responses seen. Some preliminary evidence suggests that genetic polymorphisms for antioxidant enzymes and for genes regulating the inflammatory response may modulate the effect of ozone exposure on pulmonary function and airway inflammation.

What are the effects of ozone on mortality?

Studies show:

- Ozone is associated with increased mortality

- The absolute effect of ozone on mortality is considerably higher in older adults

- The ozone-mortality relationship is most prominent during the warm season

Recent epidemiologic research has clearly demonstrated that both short-term and longer-term exposures to low concentrations of particle pollution, a common air pollutant, are associated with increased mortality. Re-examination of the data upon which those findings are based as well as new studies indicate that short-term exposure to ozone is also associated with increased daily mortality.

The study most representative of the U.S. population (Bell et al 2004) evaluated the relationships between daily mortality counts and ambient ozone concentration for 95 large U.S. communities over the period of 1987-2000. Although there was considerable heterogeneity in the magnitude of effect among the various communities, a 0.5 % overall excess risk in non-accidental daily mortality was observed for each 20 ppb increase in the 24-hour average ozone concentration (approximately equal to a 30 ppb increase in the 8-hour average) on the same day. There was evidence that the effect was greatest on the day of exposure with smaller residual effects being evident for several days. A cumulative 1.04% excess risk was observed for each 20 ppb increase in the 24-hour average concentration during the previous week. The ozone-mortality relationship was robust even after controlling for possible effects of particulate matter and other air pollutants.

Although ozone mortality risk estimates tend to be only slightly higher for the older population compared to the younger population (based predominantly on Medicare studies of people 65 and older), the absolute effect of ozone on mortality is considerably higher in older adults due to their higher baseline death rates. Even for older adults, however, the risk of dying on any given day as a result of ozone exposure is quite small. However, because of the large number of individuals at risk across the country, an effect of this magnitude has meaningful public health implications.

A preponderance of other time series studies supports the existence of an ozone-mortality relationship although with a wider range of effect estimates primarily due to the smaller sizes of the studies. An independent review of this literature by the National Research Council concludes that short-term ozone is likely to be associated with premature mortality.

Other observations made in these studies include the finding that the ozone-mortality relationship is most prominent during the warm season, with few or smaller effects in the winter. It also appears that the ozone-mortality association persists when deaths are limited to those caused by either cardiac or pulmonary disease or to those caused by cardiovascular disease alone. Risk estimates for other causes of death are generally inconsistent across studies probably reflecting the lower statistical power associated with smaller daily death rates. In the Bell study of 95 cities, the observed city-specific effect rates varied widely. The degree to which this variability reflects different ozone-mortality relationships in the different cities is not clear, but it does raise the question as to whether a single average 0.5% increase in daily mortality rates should be applied to all cities. Other unanswered questions pertain to the lowest concentrations at which these effects occur and the possible mechanisms of action responsible for increased mortality among many who spend much of their time indoors where ozone levels are generally quite low. Bell et al. divided days into those with a 24-hour average ozone concentration above and below 60 ppb and found that the relationship was similar for both subsets suggesting that the relationship is present at even very low levels of ozone. Biological mechanisms responsible for the ozone-mortality relationship are largely unknown although effects of ozone on the autonomic control of the cardiovascular system, on coagulation mechanisms, and on vasoactive substances in the blood are being actively investigated.

What are the other potential effects of short-term ozone exposure?

Other potential effects of short-term ozone exposure include:

- hospital admissions and emergency room visits for respiratory causes

- school absences

There is consistent epidemiologic evidence that ambient ozone levels are associated with other markers of respiratory morbidity, particularly during the warm season. In general, studies have reported positive relationships between short-term ozone concentrations and hospital admissions and emergency room visits for respiratory causes. Although not all studies have found significant effects, risk estimates for the majority of studies are positive. It is likely that those most at risk of serious respiratory morbidity are those with underlying respiratory disease. The evidence indicates that some of the increase in hospital visits for respiratory morbidity is due to exacerbations of asthma and possibly chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Because of the small numbers of daily hospital admissions, the effects of ozone on other subcategories of respiratory disease are not clear.

A relationship has also been observed between ozone and school absences in two studies. However, in one case the absences were related to a measure of longer-term exposure, and in the other case absences were not limited to those due to illness. Although these latter results are consistent with increased infections secondary to impaired host defense, more research needs to be done before reaching any conclusion regarding any effect of ozone exposure on respiratory infection.

Figure 9: The number of emergency or urgent daily respiratory admissions to acute care hospitals is related to estimated ozone exposure

Respiratory admission rates to 168 hospitals in Ontario, Canada during the period 1983 through 1988 are plotted against the distribution (deciles) of the daily 1-hour maximum ozone concentration, lagged by 1 day. Admission rates were adjusted for seasonal patterns, day-of-week effects, and hospital effects. Ozone displayed a positive and statistically significant association with respiratory admissions for 91% of the hospitals during the Spring through Fall seasons, but not during the Winter months of December to March when ozone levels were low. Source: Burnett et al., 1994; U.S. EPA, 1996

Ozone has been associated with daily hospitalizations for cardiovascular disease in some studies but it is not a consistent finding. A number of studies have explored the relationships between ozone and various other aspects of cardiovascular pathophysiology including heart rate variability, acute myocardial infarction, and tachyarrhythmias in those with implanted cardiac devices. Although some data are suggestive of a relationship, the results at this time do not fully substantiate a relationship between ozone exposure and adverse cardiovascular events.

At what exposure levels are effects observed?

The concentration of ozone at which effects are first observed depends upon the level of sensitivity of the individual as well as the dose delivered to the respiratory tract. The dose, in turn, is a function of the ambient concentration, the minute ventilation, and the duration of exposure. This can be expressed as a rough formula:

Dose = Ambient concentration X Level of exertion (minute ventilation) X Duration of exposure.

Thus individuals performing strenuous activity (higher minute ventilation) for several hours are likely to respond to lower concentrations than when exposed at rest (lower minute ventilation) for a shorter time. The following examples illustrate this point:

- An average young adult playing an active sport such as soccer or full court basketball outdoors for 2 hours would be expected to experience small to moderate lung function and symptom effects as well as lung injury and inflammation following exposure to 120 ppb ozone.

- If the same average young adult is at rest outdoors for the two hours, such effects would not be expected until exposures reach 300-400 ppb.

- An average outdoor laborer doing intermittent work might experience similar small to moderate lung function and symptom effects as well as lung injury and inflammation following an 8-hour exposure to 60 to 70 ppb ozone.

More sensitive individuals will experience such effects at lower concentrations while less sensitive individuals will experience these effects only at higher concentrations.

Children without asthma experience lung function decrements similar to those of young adults. But children often do not report respiratory symptoms at the lowest ozone concentrations. It is not clear whether this is the result of reduced sensitivity with regard to symptoms or whether children are less likely to recognize and report symptoms.

There are chamber studies and field studies that look at the ozone exposure level at which effects are first observed. It is not surprising that field studies show effects at much lower levels than chamber studies. This is because field studies can look at sensitive populations (including children), include exposure to all oxidant species of pollution, and may include longer exposure times. For example, field studies of agricultural workers and hikers suggest that lung function changes may be associated with prolonged ozone exposures at lower levels than those observed in chamber studies. Below are findings from key field and observational studies.

Although the results vary somewhat, several field studies suggest that the lung function of highly active asthmatic and ozone sensitive children and the exercise performance of endurance athletes may be affected on days when the 8-hour maximum ozone concentration is less than 80 ppb ozone.

Emergency room data from one study indicate that asthma attacks in the most sensitive population (e.g., children with asthma or reactive airway disease) increase following days on which the 1-hour maximum ozone concentrations exceeded 110 ppb (approximately equivalent to an 8-hour average of 82 ppb). (White et al., 1994) Another study observed increased emergency room visits for asthma on days following those when 7-hour averages exceeded 60 ppb compared to those with lower ozone concentrations. (Weisel et. al., 1995).

For effects measured in some other types of observational studies, the lowest levels at which effects are expected to occur are more difficult to identify for a number of reasons. Effects of ozone on daily mortality have been detected even when study days are restricted to those with a 24-hour average ozone concentration below 60 ppb (approximately equivalent to an 8-hour average below 90 ppb). In one study, hospital admissions for respiratory causes appear to follow a linear relationship down to background levels. (Figure 9). Limited exposure-response modeling suggests that if a population threshold for these ozone effects exists, it is likely near the lower limit of ambient ozone concentrations in the United States.

What are the effects of recurrent or long-term exposure to ozone?

One of the major unanswered questions about the health effects of ozone is whether repeated episodes of damage, inflammation, and repair induced by years of recurrent short-term ozone exposures result in adverse health effects beyond the acute effects themselves.

Daily ozone exposure for a period of 4 days results in an attenuation of some of the acute, neurally-mediated effects (e.g., lung function changes and symptoms) for subsequent exposures occurring within 1 to 2 weeks. Some health experts have, therefore, suggested that individuals living in high ozone areas may be protected from any harmful effects of long-term ozone exposure. Others suggest, however, that the attenuation of the ozone-induced tendency to take rapid and shallow breaths may blunt a protective mechanism, resulting in greater delivery and deposition of ozone deeper in the respiratory tract and other airway responses described below.

Studies including bronchoalveolar lavage and bronchial mucosal biopsies indicate that, unlike the neurally-mediated lung function changes, the processes of airway injury, inflammation, and repair continue to occur during repeated exposure. After either 4 or 5 days of exposure, markers of cell injury and increased epithelial permeability remain elevated, and an increase in airway mucosal PMN, which was not present following a single exposure, has been noted. Also, unlike the neurally-mediated effects, small airway function has been observed to remain depressed over the course of exposures and is thought to be related to the ongoing inflammation.

Studies of laboratory animals have consistently demonstrated that long-term exposure to ozone concentrations above ambient levels results in persistent morphological changes that could be a marker of chronic respiratory disease. Exposed animals experience mucous cell metaplasia and epithelial cell hyperplasia in the upper airway as well as structural changes in the lower airway including an increase in fibrous tissue in the basement membrane area and a remodeling of the distal conducting airways. In addition to airway remodeling and basement membrane changes, concurrent long-term exposure of very young primates to ozone and house dust mite allergen has been observed to result in changes in the innervation of the airways as well as an accumulation of eosinophils in the distal airways suggesting induction of an allergic phenotype. Other studies indicate that sensitization of animals to antigen occurs more easily during ongoing ozone exposures. Based on traditional measures, there is little evidence that long-term exposure in animals results in substantial changes in airway function. However, these morphological findings suggest that long-term ozone exposure might play a role in the development or progression of chronic lung disease and/or asthma.

The epidemiologic evidence is inconclusive with regard to whether long-term exposure of humans is related to chronic respiratory health effects in humans. Several cross-sectional studies have found that young adults who spent their childhoods in locales with high ozone concentrations had lower measures of lung function than those from locales with lower ozone. Similar results have not been observed, however, in a recent well-conducted longitudinal study of lung function in children or in other cross-sectional studies. Two longitudinal studies have observed associations between development of asthma and long-term ozone concentrations in subgroups of the population. These findings have not been confirmed in other longitudinal or cross-sectional studies, but they are consistent with the animal toxicological literature. Part of the difficulty in evaluating such associations has been the small number of longitudinal epidemiologic studies specifically designed to evaluate respiratory health in samples with differing ozone exposures. The mobility of the population as well as the inability to precisely estimate exposure to ozone and other potential confounders over a period of many years degrades the power of, and leads to bias in, both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies.

In spite of the inconclusive nature of the epidemiologic literature, the repeated cycles of damage, inflammation, and repair in humans and the morphological findings from the animal toxicological studies suggest that it would be prudent to avoid repeated short-term exposures, particularly in young children, until more is known about the effects of long-term ozone exposure.