Case Study: Native American Tribe uses Water Reuse

The EPA and partners have created a series of case studies that highlight the different water reuse approaches communities have taken to meet their water quality and water quantity needs. Each case study contains information about the technical, financial, institutional, and policy aspects of these water reuse systems and the communities they are located in.

On this page:

- Overview

- Context

- Solution

- Policy, Institutional, and Regulatory Environment

- Financial and Contractual Agreements

- Benefits

- Lessons Learned and Conclusions

- Background Documents

Location: Scott County, Minnesota

Water Reclamation Treatment Capacity:

- 350 million gallons (1.3 billion liters) per year - dry weather

- 550 million gallons (2 billion liters) per year - wet weather

Status: Operational since 2006

Source of Water: Treated municipal wastewater

Reuse Application: Landscape irrigation, environmental restoration

Benefits: Reduces demand on local groundwater supplies, supports biodiversity through wetland restoration

Overview

The Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community (SMSC) water reclamation facility treats municipal wastewater from Tribal residences and community business enterprises to be reused for landscape irrigation and environmental restoration. To help reduce unsustainable demands on the local aquifer, the community pursued water reuse approaches when it needed to build a new wastewater treatment facility. Annually, the community uses 10% of its treatment capacity, or about 35 million gallons (132 million liters) of treated water from its water reclamation facility to irrigate a local golf course and other landscaped areas. This reduces the demand on local groundwater supplies. The remaining treated wastewater helps support wetland restoration in the area.

Related Links

Context

The Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community (SMSC), located in Scott County, Minnesota, is a Native American tribe formalized under federal reservation status in 1969. The SMSC is recognized as a sovereign nation and is a community of the Dakota people. To support the well-being of its people, the SMSC government is responsible for infrastructure, including roads, sewers, housing, and water and wastewater treatment. The SMSC has its own public works department that builds and maintains transportation, energy, and water infrastructure. The community has legal authority over 4,000 acres (about 1,620 hectares) of land and is home to a Tribal population of 325 people. However, the community’s water use is approximately 50 times higher than what would be expected for a residential town of its size (equivalent water use to a town of 15,000) because it operates many enterprises, including two casinos, a hotel, a golf course, an event center, a community center, gas stations, a grocery store, and an organic farm. Fueled by a tradition of caring for the environment, the SMSC is aware that expanding economic activities and a growing population will put further pressure on already strained water resources in the area. Many years ago, the SMSC recognized that a sustainable water supply is imperative for future growth.

The SMSC aims to preserve its natural water resources, especially lakes, ponds, streams, and wetlands, and groundwater sources. Despite the presence of these waterbodies on the reservation, groundwater is currently the sole viable source of drinking water due to logistical and water quality issues that make the other waterbodies infeasible for use as a drinking water supply. Because of an increased demand for region-wide groundwater, the limited groundwater supply continues to be overdrafted, as groundwater extraction exceeds the sustainable yield. Models suggest a drawdown of more than 40 feet (12 meters) by 2030.

The SMSC has four wells in the Prairie du Chien–Jordan Aquifer that draw water from 200 feet to 250 feet (61–76 meters) below the land surface. These wells produce a combined 190 million gallons (719 million liters) of water per year. The groundwater is treated in the SMSC’s drinking water treatment plant, which became operational in 2019 through an innovative collaboration with the neighboring community, Prior Lake City. The groundwater is filtered, treated by reverse osmosis to remove water hardness, iron and manganese; and dosed with chlorine, fluoride, and orthophosphate. The SMSC also owns and operates a wastewater conveyance and treatment system (i.e., a water reclamation facility) to handle sewage within the community. Recognizing the issues related to overdrafts in the local aquifer, the community has taken measures to increase climate resilience, reduce water consumption, and recycle water back into the system. For example, the SMSC developed a water reclamation facility that could treat municipal wastewater to be reused for landscape irrigation and environmental (wetland) restoration.

Solution

When it needed to construct a new wastewater treatment plant in the early 2000s, the SMSC saw an opportunity to develop a facility that could reclaim its municipal wastewater to supplement its freshwater supplies. After 18 months of construction, the SMSC’s Water Reclamation Facility (WRF) became operational in 2006. Since then, the WRF has treated wastewater from Tribal residences and local enterprises and reused the water for landscape irrigation and environmental restoration. Annually, the facility typically treats about 200 million gallons of wastewater (about 757 million liters). To accommodate future growth, the annual design capacity of the WRF is larger than its current use, about 350 million gallons (1.3 billion liters) and 550 million gallons (2 billion liters) during dry and wet weather respectively.

The WRF’s reclaimed water meets high-quality water standards fit for non-potable reuse, following the requirements set by the state of Minnesota as their guide. The reclaimed water is discharged to natural surface water wetlands which store some of the water for non-potable reuse. In particular, about 35 million gallons (132 million liters) per year of the reclaimed water are used to irrigate an 18-hole golf course called The Meadows at Mystic Lake, as well as other landscaped areas. Reclaiming this water for irrigation has directly offset the use of groundwater resources for irrigation and helps to lessen groundwater overdrafting in the region. The rest of the reclaimed water flows through the surface water wetlands within the Minnesota River watershed. Because the reclaimed water is much warmer than the air, it provides a liquid water source to the wetland during the winter which attracts a variety of waterfowl to the wetland when most other waterbodies have frozen over. The SMSC’s responsible stewardship goals include maintaining the source water to its wetlands, which is achieved by the reclaimed water.

The SMSC conducted a groundwater injection and aquifer storage study to investigate whether the reclaimed water could also be used to augment local groundwater supplies. As part of these efforts, the SMSC considered various means of improving the water quality prior to injection. For example, a pilot study showed that additional treatment processes could remove recalcitrant organic compounds from the reclaimed water. However, an assessment of the subsurface geology showed a bedrock valley adjacent to the Tribal land that could impede successful injection. The bedrock would convey a large portion of the water away from the site and aquifer. Because of this issue and other concerns, full-scale injection has stalled, and the reclaimed water continues to be reused solely for irrigation and wetland preservation.

Treatment System Description

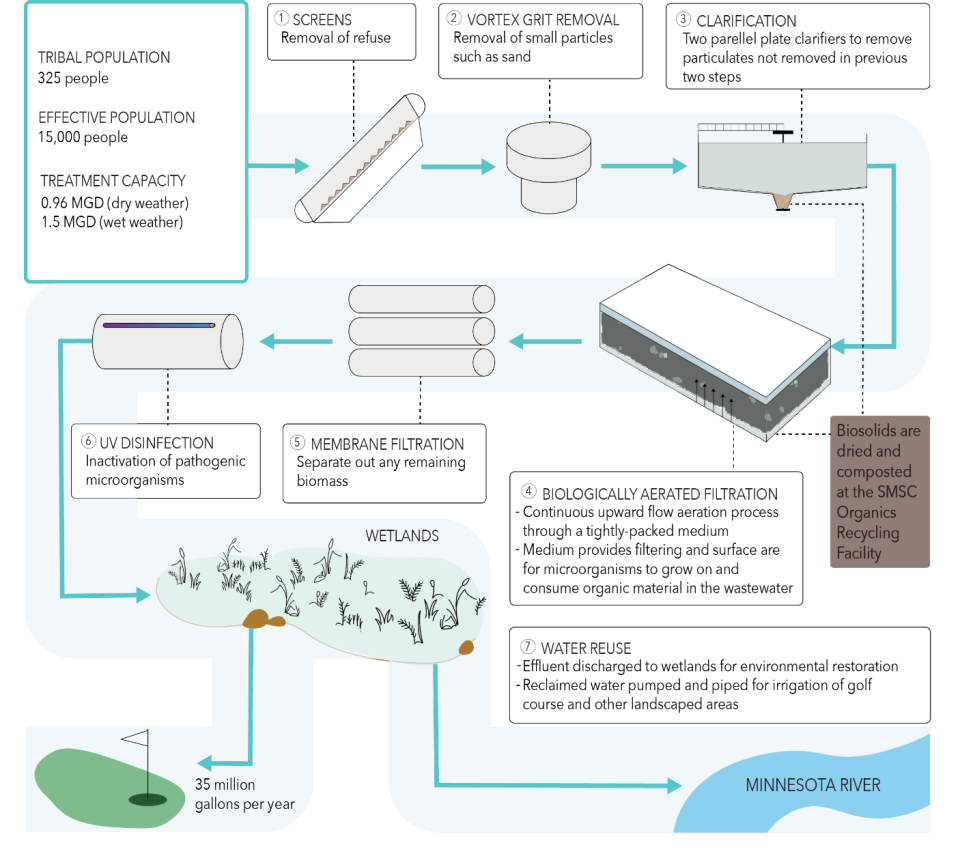

Wastewater treatment at the WRF follows a three-step purification process The WRF is designed for higher flow rates to accommodate future growth and development in the area, and includes processing of biosolids. Figure 1 illustrates the wastewater treatment process.

- Preliminary treatment: screening and clarification. Wastewater first passes through screens to remove trash and large debris, followed by a vortex grit removal system to remove small, heavy particles such as sand. To remove suspended organic material and smaller sized particles, the water enters a clarification step consisting of two parallel plate clarifiers.

- Secondary treatment: biologically aerated filtration (BAF). The clarified water now enters a continuous upward flow process, in which wastewater passes through aerated tanks (called cells) containing millions of tiny styrofoam beads (medium). The medium provides a surface for microorganisms that feed on organic material to attach and grow. The upward flow through the tightly packed medium also provides filtration. A BAF system usually employs multiple units that are rotated in and out of service depending on wastewater flow rates. Most wastewater treatment processes including BAF involve constant recirculation of the biomass to maintain the microbial community responsible for treatment. Currently, the SMSC WRF is one of less than a dozen facilities in the United States that uses the innovative BAF process for secondary treatment.

- Tertiary treatment: membrane filtration and UV disinfection. The wastewater is further filtered through a membrane (GE ZeeWeed 1000 membranes) to remove remaining biomass before entering UV disinfection to inactivate pathogenic microorganisms.

- Biosolids treatment and disposal. As of 2013, the WRF produced 136 tons of biosolids per year (123 metric tons). Following treatment, biosolids from the WRF are processed and then sent to the SMSC Organics Recycling Facility to create a high-quality compost. The SMSC Organics Recycling Facility incorporates the dried Class A biosolids into its composting processes together with other materials—like paper, food, and yard waste from residential, commercial, and municipal customers—to create a high-value compost used for landscaping throughout the community. High-quality composts, compost blends, and colored mulch are also sold commercially. The Organics Recycling Facility is operating at capacity and is therefore relocating to an industrial area in the nearby Louisville Township to accept more organic wastes. Once the permits are approved, construction is anticipated to start in 2023. The new facility is designed to handle three times as much waste as the current facility. The mulch and compost products will still be sold at the current facility location, but the current facility will no longer be used for the composting process itself after completion of the new composting facility.

Figure 2: The 35-acre (14.2-hectare) SMSC Organics Recycling Facility processes an average of 80,000 tons (72,600 metric tons) of organic material a year. Source: SMSC.

Policy, Institutional, and Regulatory Environment

The Dakota people consider their relationship with the Earth as a kinship and follow their tradition and native philosophy of planning seven generations ahead. This includes protecting and preserving the environment for future generations. The SMSC is therefore committed to being a good steward of the Earth by implementing sound infrastructure and amenities on the reservation that sustain natural resources. Part of caring for Unci Maka (Grandmother Earth) includes the preservation and conservation of groundwater and surface water resources.

The SMSC government maintains authority over its lands and government affairs and is responsible for its infrastructure. The two governing bodies are the General Council (the highest governing body, which makes important decisions and sets policies) and the Business Council. The government also includes various departments to manage local affairs. Their core cultural values and philosophies inform the way the community governs, and decision-making is intertwined with their dedication to protecting and preserving the environment.

The local SMSC Department of Land and Natural Resources is responsible for protecting the surface water and groundwater on the reservation. Activities to preserve and conserve surface waters include research, monitoring, and improving water features to provide a rich wildlife habitat and contribute to the community’s wellbeing for generations to come. This department also manages the WRF.

The SMSC is subject to Section 402 of the federal Clean Water Act, “National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System” (NPDES). A NPDES permit regulates the terms and conditions a wastewater treatment facility must meet when it discharges a specified amount of a pollutant into surface water. The SMSC’s WRF is permitted to discharge into waters of the United States through NPDES, and the WRF meets its NPDES permit. The current permit for the treatment facility at the SMSC was issued in 2019 and was valid until April 2023. Public notice for reissuance of the permit is underway and upon approval, the reissued permit will be valid for 5 years. The authorization to discharge under NPDES mandates maximum limits for quality and concentration for a range of parameters. The SMSC’s WRF staff are licensed wastewater treatment system operators through the State of Minnesota.

Financial and Contractual Agreements

Since receiving federal recognition in 1969, the SMSC has transformed from an economically distressed reservation into one of the most financially successful Native American tribes in the United States. A few Tribal initiatives, such as constructing a community building, creating a health care program, and building a childcare facility, have enhanced overall social services and brought about positive change on the reservation. Gaming operations started in the 1980s and were the basis for the community’s economic success, allowing them to responsibly steward their lands and waters. They were also able to buy more land and diversify the enterprise offerings on the reservation, including Mystic Lake Casino Hotel, Little Six Casino, Playworks, Dakotah! Sport and Fitness, Dakota Mall, The Meadows at Mystic Lake, and others.

Financial resources from gaming and non-gaming enterprises are used to pay for all the internal infrastructure of the SMSC, including but not limited to roads, water and sewer systems, power lines, parks, water and wastewater treatment, stormwater management, wellhead protection, zoning, building code enforcement, fire protection, ambulance service, police protection, and essential services in education, health, and welfare. The SMSC also fully paid for the WRF, including its current operating and capital budget. The SMSC continues to donate to charitable organizations and programs, which stems from a cultural and social tradition of helping others in need. For example, in fiscal year 2009, it donated $20.9 million.

Benefits

Water use offset: 17.5 percent of the total average treated wastewater is reclaimed to irrigate The Meadows at Mystic Lake, an 18-hole golf course, as well as other landscaped areas. This makes it unnecessary to pump any irrigation water (35 million gallons, or 132 million liters) from the already overdrafted aquifer.

Wetland restoration and preservation: The wetlands are very important to the SMSC as part of its stewardship goals. Flora and fauna such as Canada geese, muskrats, and mallards utilize the wetlands year-round. This is notable during the cold Minnesota winters when most other bodies of water have frozen over.

Nutrient recovery: The biosolids from the WRF are dried and composted at the SMSC Organics Recycling Facility. The nutrients in the biosolids, primarily phosphorus, are recovered and reused as fertilizer. This closes the recycle loop as the material is brought out to local fields and gardens in place of fertilizers sourced from outside of the reservation.

Local organic economy: The recycled biosolids from the WRF are sold as fertilizers and mulch to businesses and households.

Lessons Learned and Conclusions

Lessons Learned

Holistic and long-term commitment to Unci Maka (Grandmother Earth): The Dakota people’s history of living in harmony with their surroundings and sharing natural and material resources with others guides many of the SMSC’s decisions, especially regarding environmental stewardship activities. To be a good steward, the SMSC protects the wetlands, aquifers, prairies, and forests with which the community is intertwined. The SMSC has implemented green roofs, solar panels, organic vegetable gardens, forest and prairie management, and monitoring programs to reduce stormwater runoff and filter out pollutants, treat and reuse wastewater, and build partnerships for drinking water supply, among others. Many of these efforts and entities are tightly intertwined with—or entirely dependent on—the water that is reclaimed at the WRF.

Financial security: The thriving local economy gives the SMSC the opportunity to finance substantial infrastructure improvements, such as the WRF. The construction of the WRF and the reuse of treated wastewater was funded by public surplus over the long term and yielded additional economic and social benefits such as recovering costs from wastewater customers, generating revenue from downstream activities such as biosolids processing, and providing a water source for the wetlands which can be used for recreational activities.

Cooperation and partnership: The ability to finance public services reliably and substantially, including the supply and treatment of water, has helped the SMSC become a sought-after and reliable partner of the surrounding communities such as Prior Lake City. For example, the SMSC and Prior Lake collaborated to build a new, shared water treatment facility (in operation since 2019) to meet the needs of both growing communities for the next two decades. Using one facility, the SMSC and Prior Lake reduce their draw on groundwater and save money in the process.

Conclusions

The Dakota people’s philosophy to plan for seven generations to come shows a great degree of foresight. This future planning is evident in several of their environmental stewardship activities and projects, including their water management. Their drinking water treatment facility and the water resource sharing partnerships they have established with Prior Lake are examples of careful planning and cooperation. Another example is the pilot study on the injection of reclaimed water back into the aquifer. For nearly two decades, the treated municipal wastewater from the WRF has sustained a local wetland. Wetlands are important habitat for a variety of flora and fauna. The WRF has also afforded the community the opportunity to create more businesses (such as the sale of fertilizers and mulch) and reduced pressure on the overdrafted aquifer. The WRF has been honored with three awards for its excellence, including the Minnesota American Council on Engineering Companies’ Grand Award in 2007, the Minnesota Society of Professional Engineers’ Seven Wonders of Engineering Award in 2007, and the Minnesota Governor’s Award for Excellence in Waste and Pollution Prevention in 2007.

Background Documents

Lehto, T. 2009. SMSC celebrates 40 years of federal recognition. Native Times.

Minnesota Pollution Control Agency. Introduction to wastewater permits.

Native Green. 2022. Water management.

Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community. 2022. SMSC Water Reclamation Facility.

Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community. 2022. Organics Recycling Facility.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2018. Authorization to discharge under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System.

Water World. 2019. Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community and City of Prior Lake open joint water treatment plant.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2023. REUSExplorer: Minnesota (Treated Municipal Wastewater for Centralized Non-potable Reuse).