Climate Change Impacts on Coasts

Overview

U.S. coasts span the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic oceans as well as the Gulf of America and the Caribbean Sea. When including the coast of the Great Lakes, more than 129 million people, almost 40% of the nation's total population, live in coastal counties.1 Coastal ecosystems support many industries, provide recreational opportunities, and protect communities from storms. Coasts are also important to global trade and in providing job opportunities.

-

Damaged or lost coastal property. By 2050, up to $106 billion worth of coastal property will likely be below sea level if current trends continue.33

-

More intense rains. Heavy rainfalls associated with hurricanes increase as the climate warms.34 In 2018, Hurricane Florence produced record rainfall levels in North Carolina, causing catastrophic flooding in some areas.35

-

More tidal flooding days. Tidal flooding is increasing in some areas as sea levels rise. Some communities, including Boston, Houston, and Orlando, are seeing twice as many tidal flooding days each year as they did 20 years ago.36

-

Impacts to coastal ecosystems. Climate-driven changes can affect the feeding, breeding, and resting places for many wildlife species. For example, saltmarsh sparrows are declining on the East Coast due to increased flooding from rising seas and more extreme storms.37

-

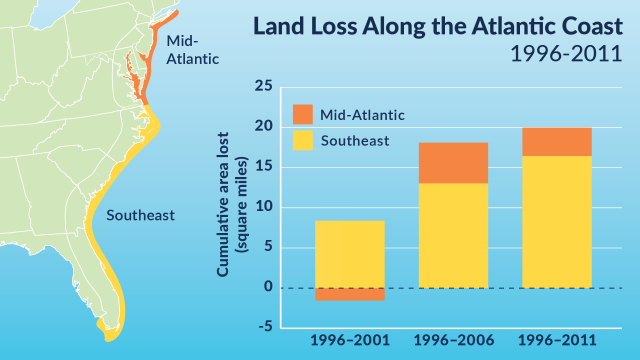

Land losses. Roughly 20 square miles of dry land and wetland became open water along the Atlantic coast between 1996 and 2011. (As a comparison, the Manhattan Island is 33 square miles.)38

U.S. coastal counties face permanent inundation and flooding threats from sea level rise, intense rains, high tide flooding, and severe storms. It is likely that hurricane intensity has also increased and that hurricanes have been intensifying more rapidly over the past four decades.2 Scientists project that as the climate warms, there will be more intense hurricanes as well as increased rainfall.3 Although there is uncertainty about where, when, and how much sea level will rise, scientists are highly confident there will be significant impacts on coastal communities even at lower-end estimates.4 Other climate threats to coasts include ocean acidification, harmful algal blooms, and saltwater intrusion.

Many communities are taking steps to protect coasts from climate change. For example, some communities are elevating buildings or constructing barriers to shield people, businesses, and property from flooding and storm surge.5,6 Others are restoring coastal habitats and using nature-based features to build coastal resilience. Many coastal cities and counties are focusing on land use planning to encourage smart growth and reduce the impacts of climate change. Yet, elsewhere, communities are relocating entirely; members of the Isle de Jean Charles Band of the Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe are planning to resettle inland after losing 98% of their tribal lands to rising seas.7, 8

Explore the sections on this page to learn more about climate impacts on coasts:

- Top Climate Impacts on Coasts

- Coasts and the Economy

- Population Impacts

- What We Can Do

- Related Resources

Top Climate Impacts on Coasts

The effects of climate change on the nation’s coasts have been observed for decades. Three key impacts of climate change are described in this section.

1. Coastal Property and Infrastructure

A growing concentration of people live in the nation’s coastal areas. In fact, while coastal counties make up only 10% of the nation’s land mass (excluding Alaska), they are home to 40% of the population.9 Climate change impacts to coastal communities affect not only human health, but also properties, infrastructure, and services.

More than $1 trillion worth of property is located within 700 feet of the coast.10 These properties’ proximity to water bodies may put them at risk of extreme weather events, hurricanes, sea level rise, and high tide flooding.11 These threats can damage or destroy property or make real estate uninhabitable. In turn, property losses potentially affect local economies by shuttering brick-and-mortar businesses, lowering tax revenues, and diverting resources from public services. Losing a home or business may also cause mental health impacts, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder.12

In addition to homes and businesses, critical coastal infrastructure is also at risk. The nation’s coasts are home to many military bases, airports, power plants, oil refining facilities, and other infrastructure. More than 60,000 miles of roads and bridges are located in U.S. coastal floodplains.14 Increased flooding of roads and bridges can delay or disrupt transportation, affecting peoples’ everyday routines, including their ability get to work or school, obtain food and supplies, and receive medical care. Increased flooding can also affect emergency preparedness and response efforts.

2. Coastal Ecosystems

The nation’s coasts include a wide range of ecosystems, such as estuaries, deltas, mangroves, marshes, beaches, and reefs. These ecosystems provide recreational opportunities and support tourism, fishing, and many other industries. They also are home to diverse species of wildlife. In addition, healthy coastal watersheds provide other benefits to society, such as improving water quality and storing carbon.

Some coastal ecosystems are already affected by rising temperatures, sea level rise, and extreme weather events.15 In addition, in a number of places nationwide, there are large dead zones where marine life cannot live. In these areas, nutrient runoff indirectly causes low oxygen levels in the water. As a result, these vast stretches of open water experience die-offs of fish, shellfish, corals, and aquatic plants. These zones are expected to increase in number and size as the ocean warms and heavier rains wash more nutrient-laden runoff into coastal waters.16

Climate change can also contribute to saltwater intrusion.17 Rising sea level and increased drought can enable saline water to advance further upstream and inland in estuaries, wetlands, and aquifers.18 Higher salinity can contaminate freshwater supplies and threaten some aquatic plants and animals.

In addition, rising sea levels and more extreme weather can increase the extent to which storm surge and high tides can cause saltwater to infiltrate low-lying areas and groundwater, which harms agriculture or drinking water supplies.

3. Land Losses

Climate change is contributing to coastal land losses, especially on the Gulf Coast.19 Rising sea levels can turn dry land into wetlands or open water. Existing wetlands can also be at risk. From 1932 to 2016, Louisiana lost more than 2,000 square miles of land area, mostly wetlands, in part due to rising sea levels.20

The loss of coastal land can have a direct impact on both the immediate environment and surrounding communities. Coastal wetlands in particular play an important role in providing habitats for fish and birds and in attenuating coastal storm impacts. As a carbon sink, wetlands help mitigate climate change by absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. When wetlands are lost, their ability to store carbon is also reduced.21 In addition, wetlands defend communities from erosion, waves, flooding, and storm surge.

For more specific examples of climate change impacts in your region, please see the National Climate Assessment.

Coasts and the Economy

The nation’s coasts are essential to local, national, and global economies. Coastal counties produce more than $9.5 trillion in goods and services each year.23 Communities on the coasts also support more than 58 million jobs in the fishing, tourism, real estate, defense, and other industries.24

Most of the goods in our stores arrive through the nation’s marine transportation system.26 In fact, more than three-fourths of all trade involves marine transportation.27

Damage to the coasts, such as from hurricanes and flooding, has negative impacts on the economy. In addition to property damage and cleanup costs, interruptions can occur in business operations and community services. Disruptions can also extend far beyond an affected area to transportation routes, energy distribution, and supply chains. Hurricane Katrina is the costliest hurricane on record, incurring damages totaling $182.5 billion in 2021 dollars.28

Population Impacts

Climate change is expected to worsen existing inequities affecting socially vulnerable populations in coastal areas. These underserved populations span many regions and groups, from the elderly in Florida to rural coastal communities to Indigenous fishing communities of Alaska. Extreme weather events have highlighted how some of these groups face heightened risks as the climate changes. For example, a disproportionate number of flood-related deaths from Hurricane Katrina were older adults.29

Not everyone will be able to prepare for or respond equally to climate change threats in coastal areas. Climate impacts may force people to elevate their homes or move. However, some people may not be able to afford to improve their homes and may be forced to move. Others may be unwilling or unable to move and may endure increasing damages. Renters, low-income households, those who face language barriers, and others may find it difficult to voice their opinions or take immediate action to preserve their home or community. In some areas, protective infrastructure might be prioritized for higher-density areas at the expense of leaving rural residents more exposed.

Many Indigenous peoples are among those coastal communities vulnerable to climate change, including those in the Southeast, the Pacific Islands, and the Northwest, as well as Alaska.30 Many Tribes are proactively planning for adaptation. In addition, some are using traditional knowledge to respond to changing environmental conditions. However, many Tribes face institutional and resource barriers that make adaptation challenging, such as limited access to their ancestral lands in vulnerable locations.31

What We Can Do

Organizations, communities, land managers, and others can take many actions to reduce the impacts of climate change on U.S. coasts, including the following:

- Identify the risks. Identifying coastal risks is the first step to managing them. EPA’s Climate Ready Estuaries program has resources to help coastal managers assess their risks.

- Work with nature. Communities can use nature-based solutions like living shorelines, green spaces, and sand dunes to help reduce the impacts of storm surge, coastal flooding, and erosion.

- Involve diverse stakeholders. Community planners can ensure all residents have a voice in coastal resilience planning, including those most vulnerable to climate impacts.

- Know if you are in a flood zone. Learn about your flood risk and the insurance protection your home needs.

- Celebrate wetlands. There are many ways you can help protect wetlands. For example, consider getting involved in a wetland, beach, or stream cleanup day.

Related Resources

- Fifth National Climate Assessment, Chapter 9: “Coastal Effects.”

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Office for Coastal Management. Provides resources and tools focused on coastal community and ecosystem resilience.

- Digital Coast. Offers data, tools, and training related to coastal issues.

- NOAA Coastal Adaptation Strategies. Provides strategies and resources for coastal adaptation planning.

- EPA: Climate Ready Estuaries. Provides guidance and assistance to help coastal managers adapt to climate change.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA): Coastal Flood Risk. Creates flood maps for coastal areas as well as tools to help communities reduce coastal risks.

- National Flood Insurance Program. Provides insurance to help reduce the socioeconomic impact of floods.

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: National Wetlands Inventory. Maps wetlands across the United States and monitors changes over time.

- Trash Free Waters. Provides information, updates, and ways to get involved in finding solutions to pollution that gets in our human-made and natural waterways.

Endnotes

1 National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Office for Coastal Management. (2024). Economics and demographics. Retrieved 8/19/2024.

2 Marvel, K., et al (2023). Ch. 2. Climate Trends. In: Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 2-16.

3 Marvel, K., et al (2023). Ch. 2. Climate Trends. In: Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, pp. 2-24-26.

4 Osler, M.S., et al. (2023). Ch. 9: Coastal Effects. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 9-14.

5 Osler, M.S., et al. (2023). Ch. 9: Coastal Effects. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 9-20.

6 Fleming, E., et al. (2018). Ch. 8: Coastal effects. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, pp. 328-332.

7 Jantarasami, L.C., et al. (2018). Ch. 15: Tribes and Indigenous peoples. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 590.

8 Carter, L., et al. (2018). Ch. 19: Southeast. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 761.

9 National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Office for Coastal Management. (2024). Economics and demographics. Retrieved 8/19/2024.

10 Fleming, E., et al. (2018). Ch. 8: Coastal effects. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 330.

11 Osler, M.S., et al. (2023). Ch. 9: Coastal Effects. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 9-12.

12 Fleming, E., et al. (2018). Ch. 8: Coastal effects. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, pp. 326.

13 Fleming, E., et al. (2018). Ch. 8: Coastal effects. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, pp. 329–332.

14 Fleming, E., et al. (2018). Ch. 8: Coastal effects. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 326.

15 Osler, M.S., et al. (2023). Ch. 9: Coastal Effects. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 9-12.

16 NOAA. Climate change likely to worsen U.S. and global dead zones. Retrieved 3/16/2022.

17 Payton, E. A., et al. (2023). Ch. 4: Water. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 4-5.

18 Fleming, E., et al. (2018). Ch. 8: Coastal effects. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 326.

19 Osler, M.S., et al. (2023). Ch. 9: Coastal Effects. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 9-5.

20 Carter, L., et al. (2018). Ch. 19: Southeast. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 775.

21 Osler, M.S., et al. (2023). Ch. 9: Coastal Effects. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 9-24.

22 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). (2021). What is a wetland? Retrieved 3/16/2022.

23 NOAA Office for Coastal Management. (2019). Economics and demographics. Retrieved 3/16/2022.

24 NOAA Office for Coastal Management. (N.D.). Coastal fast facts (pdf) (1.9 MB). Retrieved 3/16/2022.

25 NOAA Office for Coastal Management. (2019). Economics and demographics. Retrieved 3/16/2022.

26 Wolfe, K.E., and D. McFarland. (2013). An assessment of the value of the physical oceanographic real-time system (PORTS®) to the U.S. economy (pdf) (6.0 MB). NOAA.

27 NOAA Office for Coastal Management. (N.D.). Coastal fast facts (pdf) (1.9 MB). Retrieved 3/16/2022.

28 NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. (2022). Costliest U.S. tropical cyclone (pdf) (22.1 KB). Retrieved 3/16/2022.

29 Bell, J.E., et al. (2016). Ch. 4: Extreme events. In: The impacts of climate change on human health in the United States: A scientific assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 108.

30 Jantarasami, L.C., et al. (2018). Ch. 15: Tribes and Indigenous peoples. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 585.

31 Jantarasami, L.C., et al. (2018). Ch. 15: Tribes and Indigenous peoples. In: Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth national climate assessment, volume II. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 585.

32 EPA. (2021). Climate change and social vulnerability in the United States: A focus on six impacts. EPA 430-R-21-003, p. 6.

33 NOAA Office for Coastal Management. (2019). Economics and demographics. Retrieved 3/16/2022.

34 Osler, M.S., et al. (2023). Ch. 9: Coastal Effects. Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, p. 9-11.

35 NOAA National Weather Service. (2020). Service assessment: September-October 2018 Hurricane Florence and Hurricane Michael (pdf) (6.2 MB). Silver Spring, MD.

36 NOAA. (2022). The state of high tide flooding and annual outlook. Retrieved 3/16/2022.

37 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Northeast Region. (N.D.). Saltmarsh sparrows need help surviving rising tides. Retrieved 3/16/2022.

38 EPA. (2021). Climate change indicators: A closer look: Land loss along the Atlantic Coast. Retrieved 3/16/2022.