A Closer Look: Heat-Related Workplace Deaths

This feature presents data on worker deaths classified as “heat-related” in the United States and explores factors that influence exposure and vulnerability to heat.

Key Points

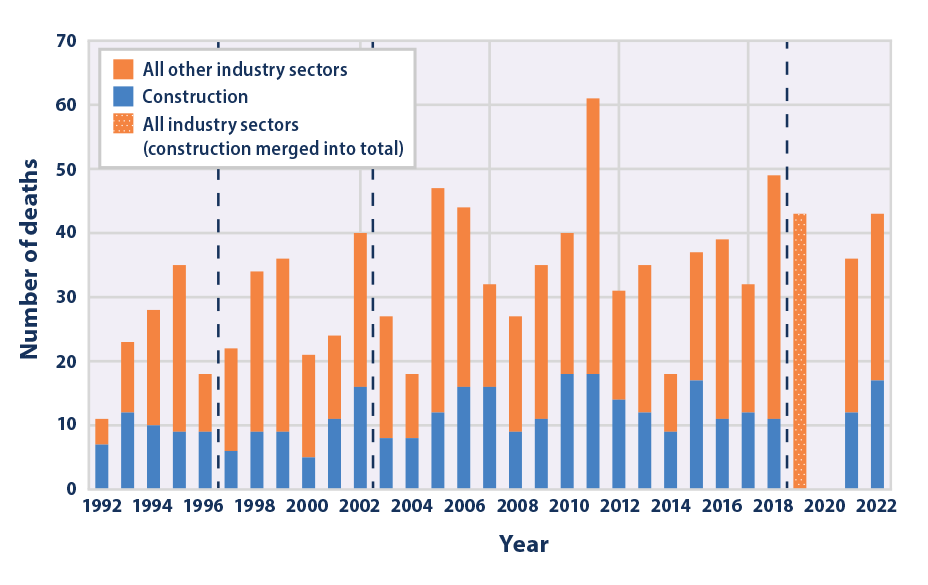

- From 1992 to 2022, a total of 986 workers across all industry sectors in the United States died from exposure to heat. This represents an average of 34 deaths per year, according to reported data (Figure 1).

- In the same period, 334 construction workers lost their lives to heat exposure on the job—meaning that the construction sector accounted for about 34 percent of all occupational heat-related deaths (see Figure 1).

- The total number of heat-related worker deaths per year has ranged from 11 (reported in 1992) to 61 (2011). The number of heat-related deaths in the construction sector peaked at 18 deaths in 2010 and 2011 (Figure 1).

- It is difficult to say for sure whether occupational heat-related deaths have increased or decreased meaningfully since 1992. This is because of high year-to-year variability and the possibility that the full extent of the problem is larger than the numbers reported here. Some deaths might not be properly categorized as heat-related, and there are reasons to believe that some work-related deaths might go unreported by employers, particularly in industries with many undocumented workers (see the “Notes” section below).

Background

Extreme heat is the leading weather-related killer in the United States (see the Heat-Related Deaths indicator).1 Over the last few decades, unusually hot summer days and nights have become more common across the contiguous 48 states (see the High and Low Temperatures indicator) and it is expected that extreme heat events will occur with greater frequency and intensity in the future.2 Thus, heat-related deaths are also expected to increase,3 although these increases may be tempered as people physiologically adapt to higher temperatures and as communities increase their resilience to heat.

Outdoor workers, particularly those engaging in strenuous physical activity, disproportionately face greater heat-related health threats.4 For example, construction workers represent only 6 percent of the total U.S. workforce, yet they account for more than one-third of all reported occupational deaths associated with heat exposure.5 Farmworkers also have disproportionately high rates of heat-related illnesses and deaths.6 Worker safety and productivity will likely be increasingly challenged as temperatures outdoors continue to rise.3 To reduce risks, employers can implement preventative measures such as ensuring access to water, training workers to recognize signs of heat-related illnesses, mandating frequent breaks and shade, providing heat-appropriate protective equipment, and limiting work during the hottest times of day.5 Several states have enacted rules to mandate these types of practices, as tracked by organizations like the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators. For more information, see the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA’s) worker safety website: www.osha.gov/heat and: www.heat.gov/pages/who-is-at-risk-to-extreme-heat.

About the Feature

This feature tracks the number of workers who died as a result of heat exposure on the job in the United States from 1992 to 2022. These data are compiled by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) from multiple sources. Many of these cases are tracked by OSHA, which requires all employers under its jurisdiction to report any work-related death. Additional information comes from other federal agencies (including the military), state agencies, death certificates and autopsy reports, and other corroborating evidence. The cause of death and other details about each fatal incident are transcribed and coded using standardized classification systems.

This feature focuses on cases whose “source of injury” was coded as “Heat—environmental”: that is, deaths caused by high temperatures that occur indoors or outdoors. Figure 1 shows the total number of heat-related deaths per year. It also shows the number of deaths specific to the construction sector, which is consistently the sector with the most heat-related deaths.

Exploring Worker Exposure and Vulnerability to Heat

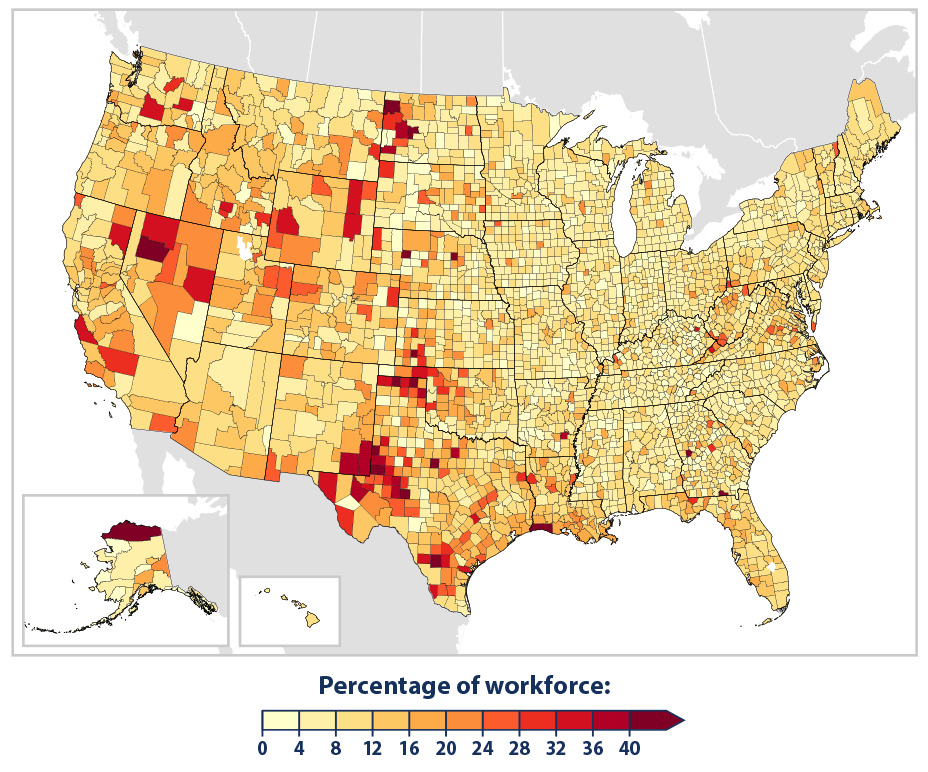

Highlighting the intersections of climate hazards, such as extreme heat, and social vulnerability can help identify people and places most at risk. Outdoor workers, particularly those engaging in strenuous physical activity, disproportionately face heat-related health threats. Between 5 million and 10 million American workers are exposed to outdoor heat beyond safe levels every year.8 Outdoor occupations are distributed throughout the United States, and they make up an especially large percentage of the workforce in certain regions (Example 1), including parts of the West, northern and southern Great Plains, and Alaska. Outdoor workers in cities may also be exposed to elevated temperatures due to the heat island effect, which can increase temperatures by 18 to 27°F during the day and 9 to 18°F at night in urban areas compared with outlying areas.9

Notes

This feature counts deaths in workplaces of all types and sizes. It is not limited to establishments that fall under the jurisdiction of OSHA or other specific agencies.

Several factors influence the ability of this feature to estimate the true number of occupational heat-related deaths. As discussed in the Heat-Related Deaths indicator, deaths classified as heat-related may have other important contributing causes. Conversely, deaths associated with extreme heat are not always reported as such. Unlike the Heat-Related Deaths indicator, though, this feature is based on many types of corroborating evidence in addition to death certificates. A fraction of deaths may go unreported by employers, may not be properly categorized as heat-related, or may not be attributed to an occupational cause if the death occurs off the job site (for example, after the employee has left work for the day).11 The underreporting rate is believed to be larger in industries that tend to have more undocumented or short-term workers.12

This feature uses death counts rather than death rates. Reporting the total number of deaths per year is useful for communication because it puts the exact number of lives in perspective, but it does not account for changes over time in population or sector-specific employment. Improvements to the tracking of worker-related fatalities include standardization of employer and state reporting of work-related heat deaths.13 Reporting of illnesses and injuries must be immediate to ensure that illnesses and deaths are not mis-classified or missed altogether.14

Data Sources

Data for this feature were provided by BLS. The data in Figure 1 are publicly available on the BLS Injuries, Illnesses, and Fatalities website at: www.bls.gov/iif/home.htm. Data for the outdoor workers map figure came from BLS’s Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages: www.bls.gov/cew/downloadable-data-files.htm.

Technical Documentation

References

1 NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). (2023). Weather related fatality and injury statistics. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from www.weather.gov/hazstat

2 Marvel, K., Su, W., Delgado, R., Aarons, S., Chatterjee, A., Garcia, M. E., Hausfather, Z., Hayhoe, K., Hence, D. A., Jewett, E. B., Robel, A., Singh, D., Tripati, A., & Vose, R. S. (2023). Chapter 2: Climate trends. In USGCRP (U.S. Global Change Research Program), Fifth National Climate Assessment. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH2

3 IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). (2022). Climate change 2022—Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: Working Group II contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (H.-O. Pörtner, D. C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E. S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, & B. Rama, Eds.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844

4 Hoegh-Guldberg, O., Jacob, D., Taylor, M., Bindi, M., Brown, S., Camilloni, I., Diedhiou, A., Djalante, R., Ebi, K. L., Engelbrecht, F., Guiot, J., Hijioka, Y., Mehrotra, S., Payne, A., Seneviratne, S. I., Thomas, A., Warren, R., & Zhou, G. (2018). Chapter 3: Impacts of 1.5oC global warming on natural and human systems. In IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty (pp. 175–312). Cambridge University Press. www.ipcc.ch/sr15/chapter/chapter-3

5 Dong, X. S., West, G. H., Holloway-Beth, A., Wang, X., & Sokas, R. K. (2019). Heat-related deaths among construction workers in the United States. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 62(12), 1047–1057. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.23024

6 Jay, A. K., Crimmins, A. R., Avery, C. W., Dahl, T. A., Dodder, R. S., Hamlington, B. D., Lustig, A., Marvel, K., Méndez-Lazaro, P. A., Osler, M. S., Terando, A., Weeks, E. S., & Zycherman, A. (2023). Chapter 1: Overview: Understanding risks, impacts, and responses. In USGCRP (U.S. Global Change Research Program), Fifth National Climate Assessment. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH1

7 BLS (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). (2024). Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI). Retrieved September 10, 2024, from www.bls.gov/iif/home.htm.

8 Milken Institute School of Public Health. (2017). Hazard zone: The impact of climate change on occupational health. Retrieved April 29, 2024, from https://onlinepublichealth.gwu.edu/resources/impact-of-climate-change-on-occupational-health

9 National Integrated Heat Health Information System. (2024). Who is most at risk to extreme heat? Retrieved April 1, 2024, from www.heat.gov/pages/who-is-at-risk-to-extreme-heat

10 BLS (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). (2024). Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW) [Data set]. Retrieved April 1, 2024, from www.bls.gov/cew/downloadable-data-files.htm

11 Hayden, M. H., Schramm, P. J., Beard, C. B., Bell, J. E., Bernstein, A. S., Bieniek-Tobasco, A., Cooley, N., Diuk-Wasser, M., Dorsey, M. K., Ebi, K., Ernst, K. C., Gorris, M. E., Howe, P. D., Khan, A. S., Lefthand-Begay, C., Maldonado, J., Saha, S., Shafiei, F., Vaidyanathan, A., & Wilhelmi, O. V. (2023). Chapter 15: Human health. In USGCRP (U.S. Global Change Research Program), Fifth National Climate Assessment. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH15

12 Tigchelaar, M., Battisti, D.S., & Spector, J.T. (2020). Work Adaptations Insufficient to Address Growing Heat Risk for U.S. Agricultural Workers. Environ Res Lett., 15(9):094035. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/ab86f4

13 OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration). (2022). Heat: Standards. Retrieved November 1, 2022, from www.osha.gov/heat-exposure/standards

14 Orrenius, P. M., & Zavodny, M. (2009). Do immigrants work in riskier jobs? Demography, 46(3), 535–551. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0064