About the Health of the Salish Sea Report

In 2000, EPA and Environment Canada (now Environment and Climate Change Canada) agreed to work together to address cross-border environmental issues facing the Georgia Basin-Puget Sound marine ecosystem, now known as the Salish Sea. This agreement required our two agencies to develop action plans and report to the public on the health of our common ecosystem.

Our first report was published in 2002, followed by a second report in 2005. This website represents the current version of our report. It has been updated periodically since 2013 to reflect new information and data. The 2020 version updates information and data for all 10 ecosystem indicators.

There is some intentional overlap of information between this report and other reports that are available - most notably the Puget Sound Partnership's Vital Signs and the recent State of the Salish Sea report coordinated by the Salish Sea Institute at Western Washington University.

This report is unique in its focus on the entire Salish Sea ecosystem with an emphasis on collaboration across the U.S.-Canada international border and across various levels of government, academic institutions, non-profits, First Nations and Puget Sound Tribes.

How to Use this Report

Just as doctors use blood pressure to learn about a person's overall health, scientists can learn about an ecosystem's overall health by studying certain plants, animals, and other environmental measures.

In this report we study trends for 10 environmental indicators (e.g. air quality, Chinook salmon) that help give us a better picture of the current environmental, economic, and social well-being of our Salish Sea watershed.

You don't need to read the indicator summaries in any particular order. No single indicator is representative of all that's happening, but as you read about each one you'll begin to see and understand how they're connected.

We've assigned a green, red, or yellow icon (see legend) to each indicator that lets you know whether the overall status is improving, declining, or neutral (unchanged).

Our findings for each indicator address the following questions:

- What's happening?

- Why is it important?

- Why is it happening?

- What's being done about it?

You will also see tips for what you can do to help, links for related information, and scientific references used to support our findings.

Our findings will be updated periodically.

Causal Framework

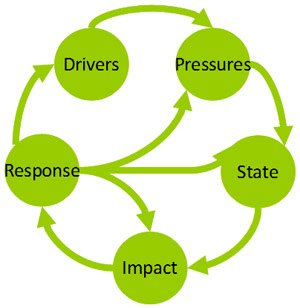

A causal chain analysis is a scientific approach for linking the cause of a problem with its effects.

This report uses a framework called Drivers-Pressures-State-Impacts-Response (or DPSIR) to define the causal links between human activities (drivers) and the stress or pressure they can put on the ecosystem, changes in the state of the ecosystem, and impacts to the ecosystem.

- Drivers = social, demographic and economic forces.

- Pressures = human activities.

- State = measured conditions, trends.

- Impacts = significance.

- Responses = actions, decisions, adaptations.

Society can then respond with management actions that regulate the driver, pressure, state, or impact.

Indicators used in this report were selected based on criteria to ensure scientific validity, practicality, reliability and relevance to regional ecosystem goals. Preference was given to transboundary indicators that were included in our previous reports, as well as those compatible with indicators reported through the Puget Sound Partnership's Vital Signs.

Interconnectedness Among Indicators

While we report on the indicators individually, many of the indicators in this report are connected. Within an ecosystem, changes to any one component can influence other components. For example, Chinook salmon abundance and the population size of the Southern Resident Killer Whales are states that we measure as indicators in this report. Because Southern Resident Killer Whales feed on Chinook salmon, a change in the abundance of salmon can impact Southern Resident Killer Whale populations, and vice versa.

Another example of interconnectedness among the indicators includes linkages between freshwater quality and marine water quality. Freshwater streams eventually meet the marine environment along the coast. High levels of nutrients in freshwater can lead to blooms of marine algae that eventually decompose in deeper layers of marine water, using up the marine water’s dissolved oxygen.

Shellfish and swimming beach accessibility are influenced by freshwater and marine water quality. Shellfish beaches must meet strict standards if the shellfish harvested from the areas are intended for consumption. Swimming beaches also must meet minimum water quality standards in order to be available for recreational use.

Connections among the indicators represent opportunities. When actions/responses to ecosystem pressures are implemented, they may improve the state of connected components within the ecosystem. In the indicators that we describe in this report, many of the actions that we highlight in the “What’s being done about it” sections will reduce pressures on the ecosystem and will benefit more than one indicator.

Local and Indigenous Knowledge

Throughout this report you will see sections are called "Sustainable Perspectives." These sections refer to local and Indigenous knowledge (also called traditional ecological knowledge) which is built over generations as people learn from the land and sea they depend on for their food, materials and culture, and directly interact with the ecosystem over a long time.

While at times the Western scientific perspective may be different from the local and Indigenous knowledge perspective, both have a great deal to offer one another. Working together is the best way of helping us achieve a better common understanding of nature.

Local and Indigenous knowledge:

- Increases the timeline of available information.

- Provides a more holistic view of ecosystem interactions.

- Helps answer the question, "Why is it important?"

This report presents the Sustainable Perspectives, including Indigenous Knowledge contributions, that were gathered originally for the 2013 version of this report with guidance from our Steering Committee (see Acknowledgements). Going forward, a new approach for presenting local and Indigenous Knowledge within the Salish Sea Ecosystem Indicator updates is being explored. The future approach to presenting Indigenous Knowledge in Salish Sea Ecosystem Indicator updates will be determined through discussions with Indigenous partners living in the Salish Sea region.

Indigenous people of the world possess an immense knowledge of their environments, based on centuries of living close to Nature. Living in and from the richness and variety of complex ecosystems, they have an understanding of the properties of plants and animals, the functioning of ecosystems, and the techniques for using and managing them...

...Equally, people's knowledge and perceptions of the environment, and their relationships with it, are often important elements of cultural identity.

Source: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization

About the Data

This report updates previous Puget Sound-Georgia Basin ecosystem indicator reports (in 2002 and 2005) and the previous Salish Sea Ecosystem indicator report (2013) and builds on the information to increase relevance to ecosystem health, including human well-being.

A number of current publications report on environmental conditions in the Salish Sea. This report draws on existing publicly-available information, including agency technical reports, scientific sampling from Canadian and U.S. sources, and scientific work by non-governmental organizations.

Related Information

- U.S.-Canada Cooperation in the Salish Sea

- Canada-U.S. Cooperation on Georgia Basin and Puget Sound Ecosystems

- Canada - Sharing Knowledge on Cumulative Effects in the Salish Sea Ecosystem

- Puget Sound

- Health of the Salish Sea as Measured Using Transboundary Ecosystem Indicators (2014)

- Salish Sea Institute