Southern Resident Killer Whales

Updated June 2021 based on data available through December 2020.

- About Southern Resident Killer Whales

- What's Happening?

- Why Is It Important?

- Why Is It Happening?

- What's Being Done About It?

- Six Things You Can Do To Help

- References

About Southern Resident Killer Whales

Killer whales, or orcas, are top predators and cultural icons of the Salish Sea. During the spring, summer and fall months, killer whales can be seen regularly in these waters.

Southern Resident Killer Whales have been listed as endangered species in both the U.S. and Canada, and their population is closely tied to the overall health of the ecosystem.

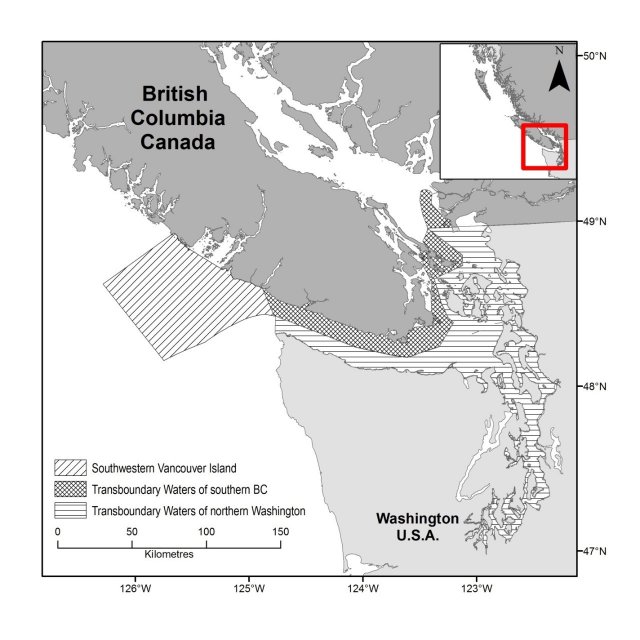

Critical Habitat

Critical habitat is especially important to maintain as it provides the features, functions and attributes required to support the species’ survival or recovery. Such habitat provides for sustained feeding and foraging, resting, socialization, reproduction, rearing, and migration.

Coastal watersheds that are not currently designated as critical habitat are also important for Southern Resident Killer Whales and their prey. Southern Resident Killer Whale critical habitat in Canadian waters was expanded in 2018, and in the United States, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is proposing to expand Southern Resident Killer Whale habitat beyond the Salish Sea.

Social Organization

Killer whale societies are organized into a series of social units according to maternal genealogy. How much each unit is related to another gets progressively weaker from the smallest social unit (matriline) through the largest (community).

Matriline

Matriline is the smallest killer whale social unit. A matriarch (older female) and all of her descendants (including sons, daughter, and grandchildren) are referred to as a matriline. Sons and daughters stay with their mother throughout their lives, even after they have offspring of their own. In 2010, Southern Resident Killer Whales were organized along 19 matrilines, and more recent estimates report that up to 25 matrilines may now exist.

Pod

A pod is a group of related matrilines that travel, forage, socialize, and rest together. As pods grow in size over time, they may split into new pods. Southern Resident Killer Whales are comprised of three pods: J-Pod, K-Pod and L-Pod.

Clan

A clan is a group of pods that share similar calls or dialects. Pods with very similar dialects are more closely related than those with different features in their dialects. All Southern Resident Killer Whales belong to J-Clan.

Community

Community is the top level of killer whale social structure. Resident killer whales that share a common range and that associate at least occasionally are considered to be members of the same community. Pods from one community have rarely or never been seen to travel with those from another community even though their ranges partly overlap. There are two communities found in the Salish Sea: Northern Resident Killer Whales and Southern Resident Killer Whales.

Ecotype

Although they are currently recognized as a single species, three distinct ecotypes of killer whale can be found in the Salish Sea. These ecotypes of killer whale do not interbreed, and differ in their behavior, calls, genetics, morphology, and prey preferences. Resident killer whales (split into Northern and Southern residents) primarily eat salmon, while Transient killer whales (also called Bigg’s killer whales) eat marine mammals and seabirds. The third ecotype of killer whale, Offshore killer whales, eat sharks and other fishes and are rarely seen in the Salish Sea. Differences in appearance, such as dorsal fin shapes and markings on the backs of the whales, can be used to tell the ecotypes apart.

Sustainable Perspectives

Killer whales and coastal Indigenous people have lived together in the Salish Sea for at least 5000 years.

Although remains of many marine mammals can be found at historical Salish village sites, killer whales are rarely found at these sites. This has been attributed to their special significance in aboriginal culture. In British Columbia, non-First Nation anglers once considered killer whales to be nuisances and competition for salmon. About 1 in 4 killer whales that were captured in the 1960s and 1970s showed evidence of having been previously shot and wounded.

By the late 1960s, attitudes toward killer whales shifted as people around the world observed captive killer whales as intelligent mammals. By the 1970s, the North American environmental movement helped foster compassion for killer whales. In 1980, increased public interest supported the first commercial whale watching excursions in Johnstone Strait. Now whale watching generates hundreds of millions of dollars annually in the U.S. and Canada.

Counting Killer Whales

The counting of individual killer whales began in 1972 and 1973 with the collection of information on killer whales and their movements near Vancouver Island. Using photographs of killer whales showing identifying features, including some submitted by citizens. Researchers at Fisheries and Oceans Canada were able to develop the first estimates of killer whale population size for British Columbia. Those early researchers wrote in 1976 that their efforts would be enhanced by the further efforts planned in Washington state.

The photo-identification studies that started in the State of Washington in 1976 have now continued annually for 44 years. The Center for Whale Research records encounters with killer whales, including the Southern Resident Killer Whales. Researchers now know about each individual in the Southern Resident Killer Whale population. According to the Center for Whale Research, the Southern Resident Killer Whales are now the best-studied marine mammals in the world.

On January 24, 2020, the Center for Whale Research reported that L41, one of the most prolific breeding males from L-pod, had gone missing and is now feared dead. A confirmed loss of another whale would leave the killer whale population at 72 animals. Immediately after the published update, local media in British Columbia and Washington both reported on the discouraging news.

The Seattle Times described the whale’s contribution to the Southern Resident Killer Whale population: "L41 fathered 21 orca babies with 11 different females."It is not clear yet if L41 is truly gone, as the Vancouver Sun's interview with a marine mammal researcher noted that, "males help locate prey and spread out and communicate information."

The Center for Whale Research summed up the hope of many in the Salish Sea in a follow-up media release: "We are hopeful that L41 is alive somewhere and returns to the subgroup, but he did live to a ripe old age and fathered more baby whales than any other whale in the community."

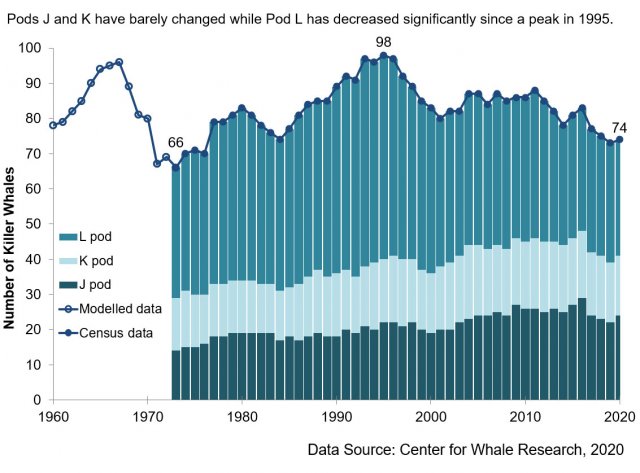

In the fall of 2020, the Center for Whale Research reported two killer whale births that were announced widely in American, Canadian, and even the international media. The health of the calves appear good and they have been named Phoenix J57, birthed by Tahlequah J35; and Crescent J58, birthed by Eclipse J41. These births mark the first since the last healthy recorded birth to the southern residents in May 2019, and bring the total SRKW population to 74 - including 24 in J Pod, 17 in K Pod and 33 in L Pod.

What's Happening?

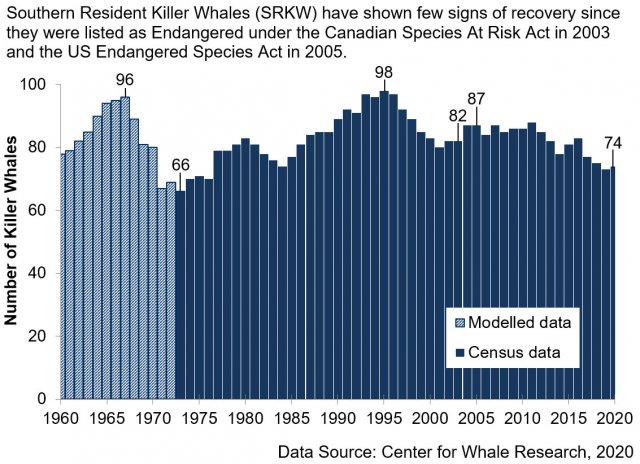

From 1973 to 2019, the Southern Resident Killer Whale population showed periods of both growth and decline. When researchers conducted the first population census in 1973, 66 whales were sighted. It is unknown what historic population sizes may have been before researchers started tracking the Southern Resident Killer Whale population.

The population increased by 48% relative the first whale census in 1973, to a count of 98 individuals in 1995, and then dropped 16% to a count of 80 individuals in 2001, prompting the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) to designate the Southern Resident Killer Whales as Endangered. The U.S. began the process of listing them as endangered species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), with the listing finalized in 2005. In Canada, Southern Resident Killer Whales were listed under the new Species at Risk Act legislation in 2003.

By December 2020, the Southern Resident Killer Whale population had declined to a 40-year low count of 74 individuals. This is more than a 25% decline from the observed peak population size in 1995. There were killer whale births at the start of 2019, with one birth occurring in January and another in May. These births raised the population to 76 individuals, which was encouraging. However over the remainder of 2019, three whales were declared missing and presumed deceased. Now the number of Southern Resident Killer Whales is approaching the observed lowest count, recorded in 1973.

The three pods within the Southern Resident Killer Whale population have shown different dynamics in the number of whales over time. Since the observed peak population size of 98 Southern Residents in 1995, the size of K-pod has remained consistent with about 17 individuals. The size of J-pod increased after 1995 to a peak of 29 members in 2016, but most recently the size of J-pod has returned to 24 individuals, which is the same size as it was recorded in 1995.

Since 1995, L-pod has lost 25 individuals, contributing the most to the overall decline in the population count for Southern Resident Killer Whales. L-pod has the highest proportion of older females. Older female killer whales contribute to a pod’s success by assisting with hunting and increase the chances of survival of juveniles, but older females that are no longer reproducing limit the ability to add new juveniles to the pod’s population. L-pod also appears to have high juvenile mortality and a male sex-ratio bias among juveniles. These factors may represent further challenges to the recovery of the L-pod.

Why Is It Important?

The health of killer whale populations is important for many reasons. Killer whales are culturally, spiritually, and economically important to the Salish Sea. They are featured prominently in the stories and art of the Coast Salish people and other Indigenous peoples of the northwest coast of North America. And, for some Salish peoples, killer whales are family members that live under the water.

Killer whales are viewed as an indicator species for the Salish Sea. The decline in local killer whale populations may indicate stressors that eventually will affect the whole ecosystem.

Killer whales are also important for local tourism. In 2008, the total expenditures from whale watching in British Columbia was estimated at $118 million USD. A 2013 survey of Salish Sea whale watching companies ranked killer whales as the most important wildlife species for their clients and company marketing. As of 2018, whale watching in the Puget Sound region alone provides an economic contribution of over $216 million USD annually and supports over 1,800 jobs.

Why Is It Happening?

Recent declines in Southern Resident Killer Whale populations are linked to reduced prey availability, and other threats such as chemical pollution, or acoustic and physical disturbance from vessels and other noise sources. These factors have an even greater impact on the Southern Resident Killer Whale population when they are combined than could be predicted by studying any one factor by itself. Studies have shown that all threats need to be a part of population size models for Resident Killer Whales in order to match the observed changes in Resident Killer Whale abundance over time.

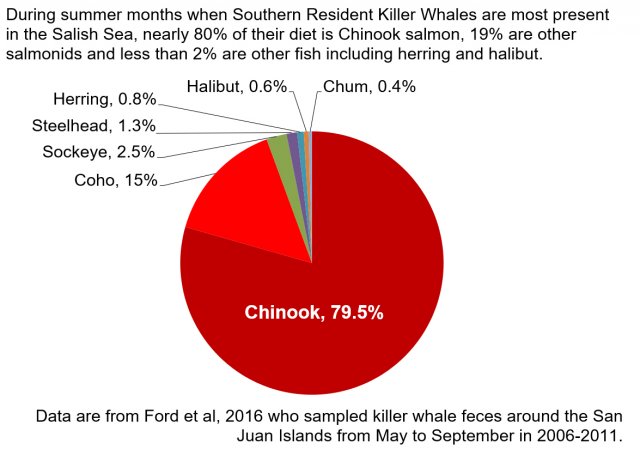

Southern Resident Killer Whales rely heavily on healthy populations of salmon – particularly Chinook – which are declining across the Salish Sea and Pacific coast. For all of June 2019, Southern Resident Killer Whales were not spotted in the Salish Sea for the first time on record. The Southern Resident Killer Whales did arrive in July 2019, though. Changes in the spring presence patterns for Southern Resident Killer Whales in the Salish Sea has been linked to Chinook salmon abundance patterns for the period of 1994-2016. An overall change in the Salish Sea community is happening however, as the observed presence of transient killer whales, which eat marine mammals rather than fish, increased from 2011-2017 in the Salish Sea.

Understanding the problem of prey abundance is complicated because most Southern Resident Killer Whale pods spend most of the time each year outside the Salish Sea, in environments where it can be challenging to carry out research. While conditions in the Salish Sea and its watersheds are important to enhance and protect, conditions in the Pacific and coastal watersheds from Central California through Vancouver Island are also important to enhance and protect. Southern Resident Killer Whales also forage near the outlets of the Sacramento River, the Klamath River, and the Columbia River watersheds, which historically supported large runs of salmon that the killer whales rely on as food.

Changing age demographics and gender ratios within the small Southern Resident Killer Whale population can compound these factors and have pronounced influence over social dynamics such as mating, group foraging, and social care of calves. Further, the greater genetic diversity loss in stable or declining populations and inbreeding is becoming an increasing concern for Southern Resident Killer Whale survival and reproductive success.

An estimated 48 Southern Resident Killer Whales were removed from the Salish Sea between 1962 and 1977, due to live capture activities for aquariums all over the world. Washington and British Columbia served as the primary source of captive killer whales because inland waters offered fewer escape routes, shallower waters made netting easier, and a large network of shore observers provided updates on movements of the whales.

Current Threats to Killer Whale Recovery

Prey Availability

Survival and birth rates in Southern Resident Killer Whales have shown a close correlation with coast-wide abundance of salmon. The abundance of their preferred prey, Chinook salmon, has declined from historical levels in the Salish Sea. Fraser River Chinook salmon have been shown to make up about 80% of killer whales’ summer diet when they are in the Salish Sea, and Fraser River populations are currently of conservation concern due to substantial declines over the last decade. In the fall, Southern Resident Killer Whale pods in Puget Sound show more Chum and Coho salmon in their diet. Low Chinook salmon availability has been linked to failed pregnancies in Southern Resident Killer Whales.

Southern Resident Killer Whales also consume Chinook salmon from the Columbia, Sacramento, and Klamath rivers along with other coastal river systems outside of the Salish Sea ecosystem, and a small proportion of other fish species throughout their range. These other river systems contribute prey during winter months when coastal foraging is particularly important to local pods of killer whales, making up the largest portion of the Southern Resident Killer Whale’s annual diet.

Pollution and Contaminants

High levels of persistent organic pollutants (e.g. PCBs and DDT, which were banned from use in Canada and the U.S. long ago) and newer pollutants like those found in flame retardants (PBDEs), may be preventing the population of Southern Resident Killer Whales from increasing at a rate required for recovery. Individuals have been found to carry some of the highest PCB concentrations reported in animals, with levels in blubber exceeding those known to affect the health of other marine mammals. Other contaminant levels, such as the levels of DDT and PBDEs, are also found in high levels, especially in juvenile killer whales.

When trapped in blubber, contaminants have little impact on the killer whale’s health. However, when killer whales are food-deprived, they rely on their blubber to survive. When this fat is used, harmful pollutants accumulated in the blubber over time are released into the whales. These pollutants, in addition to malnutrition, may cause pregnancy failure in Southern Resident Killer Whales and may affect the killer whale’s immune system function.

Vessel Traffic, Noise and Risk of Oil Spills

The cumulative impacts of vessel presence and noise may interfere with the ability of Southern Resident Killer Whales to communicate and find food. Southern Resident Killer Whales may avoid areas in their foraging range that have high levels of vessel disturbance and may spend additional energy and swim faster to avoid vessels. Studies indicate that whales expend more energy and find less food when vessels are present than when they are not present, making it harder to find enough food for growth and successful reproduction when salmon are scarce. Whales adapt and find prey when there are high noise levels in their background environment by increasing the loudness of their calls, which may use additional energy while they hunt for food.

What's Being Done About It?

Many agencies and groups are working to address threats to the Southern Resident Killer Whales by focusing on efforts that address prey availability, environmental contaminants, acoustic and physical disturbance from shipping and boat traffic, and oil spills. In recent years, governments in the United States and Canada have both contributed over one billion dollars to efforts aiming to protect and recover Southern Resident Killer Whales, in addition to ongoing spending specifically targeted at salmon recovery.

Examples

Below are examples of the type of work being done by government agencies to help protect killer whale populations:

Conducting Research, Science and Monitoring

Current information is essential to inform decision-making, adaptive management and implementation of actions to recover the Southern Resident Killer Whales. It will be important to use an adaptive management approach to track effectiveness of implemented actions, assess unintended consequences, monitor ongoing ecosystem change and adjust future policies and investments based on the findings. Continued monitoring of killer whales under existing sightings networks and observation programs in Canada and the United States contributes updated and current information on the population size of the killer whales as they move.

Coordinating Marine Mammal Response Networks

Several partners in Canada agreed that there was a need to unite marine mammal response networks across Canada, in efforts to support the work of Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s response activities. The Canadian Marine Animal Response Alliance brings together several organizations across Canada to further rescue, research, and outreach activities.

Funding Investments from the United States

In May 2019, the Washington State Governor signed 5 orca recovery bills into law, which aim to decrease vessel noise and traffic, educate boaters about whale watching, more safely transport oil, support Chinook salmon populations, and decrease toxics pollution. The Governor’s 2019-2021 operating budget includes $1.1 billion USD for enforcement of these laws, salmon habitat restoration, salmon hatcheries, and toxics cleanup and prevention.

Funding Investments from Canada

In 2018, the Government of Canada introduced its 5-year, $167.4 million (CAD) Whales Initiative. Funds from this initiative are used to improve killer whale prey availability, reduce vessel disturbance, increase environmental monitoring for whales and noise, strengthen compliance and enforcement with whale-related regulations, and build partnerships with other organizations. These funds are in addition to Canada’s 2016 $1.5 billion (CAD) Oceans Protection Plan, to help protect Canadian waters and marine life, including killer whales. In October 2018, another $61.5 million (CAD) was allocated by Fisheries and Oceans Canada for additional measures to protect and support the recovery of the Southern Resident Killer Whale.

Collaborating to Increase Understanding

The U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries is working with Fisheries and Oceans Canada to evaluate a report by an independent science panel that evaluated effects of salmon fisheries on Southern Resident Killer Whales. They are also working toward understanding other potential factors such as where the whales are in the winter when they are outside of the Salish Sea, demographics, mating patterns and inbreeding effects.

Collaborating to Inform Management Actions

Several initiatives have been focused recently on protecting Southern Resident Killer Whales including:

- The Washington State Governor established the Southern Resident Orca Task Force in March 2018 to develop recommendations for killer whale recovery. This task force invited participants from many U.S. states, local governments, and Canadian government agencies.

- In 2018, the Government of Canada formed several technical working groups focused on the key threats to Southern Resident Killer Whales, with representatives comprised of policy, technical and scientific experts from the federal government, Indigenous groups, environmental groups, and industry. Recommendations from these working groups, along with consultations with Indigenous groups, stakeholders, environmental organizations and the public, led to the implementation of a number of additional management measures in 2019 for the Southern Resident Killer Whale. Management measures focused on prey availability and acoustic and physical disturbance including the creation of three interim sanctuary zones in Canadian Southern Resident Killer Whale critical habitat. These efforts continue, with implementation of enhanced measures to protect Southern Resident Killer Whales.

- The Vancouver Fraser Port Authority is leading the Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation (ECHO) Program to better understand and manage the impact of shipping activities on at-risk whales throughout the southern coast of British Columbia. The ECHO program also has several U.S. and Canadian agency collaborators.

- In 2019, a conservation agreement for Southern Resident Killer Whales under Section 11 of the Government of Canada's Species at Risk Act was signed with the goal to reduce the acoustic and physical disturbance from large commercial vessels and tugs that operate in killer whale critical habitat. The five-year agreement was the first for a marine aquatic species and was signed by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Transport Canada, the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, the Chamber of Shipping of British Columbia, the Shipping Federation of Canada, Cruise Lines International Association, the Council of Marine Carriers, the International Ship Owners Alliance of Canada, and the Pacific Pilotage Authority.

Whale Watching Laws, Marine Mammal Regulations, Interim Measures and Guidelines

The Canadian Government, U.S. National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration, and Washington State have adopted vessel regulations to reduce vessel disturbances and manage traffic. Organizations such as Straitwatch (for Victoria and the Southern Gulf Islands) and Soundwatch (for the San Juan Islands) provide details about these rules and guidelines for vessels near whales. Be Whale Wise provides up to date information on guidelines and regulations for boating around marine mammals. The measures that are in place include:

- As of May 2019, a Washington State law to protect Southern Resident Orca Whales restricts boats and kayaks to slow to no-wake speeds (slower than a speed of 7 knots) within a half-nautical mile of the Southern Resident Killer Whales, though there are several exemptions for safety and other reasons.

- Also enacted in May 2019, Washington State law requires that vessels in Washington must stay at least 300 yards away from either side of killer whales and 400 yards behind or in the advancing paths of killer whales, and must disengage engines if the separation distance is less than this.

- In 2018, amendments to the Marine Mammal Regulations under Canada’s Fisheries Act make it mandatory to stay 200 metres away from all killer whales in Canadian Pacific waters year-round. These regulations along with those for other marine mammals and any exceptions that may apply can be explore online at Fisheries and Oceans Canada's website.

- From June 2019 to October 2019, through an Interim Order under the Canada Shipping Act, the Government of Canada required all boaters to stay a minimum distance of at least 400 metres away from all killer whales when in the Canadian critical habitat for the Southern Resident Killer Whales. Canada also put Interim Sanctuary Zones in place in 3 locations (Swiftsure Bank, Pender Island and Saturna Island). These measures were in effect from June 1, 2019 – October 31st, 2019. Consultations on the continuation of these measures were held at the end of 2019 and the measures were renewed in 2020.

Improving Land Leasing Activities

The Washington Department of Natural Resource's Aquatic Reserves Program is working to protect aquatic environments from aquatic land leasing activities, with emphasis on protecting habitat and species such as killer whales. As well, the State of Washington enacted legislation to phase out the aquaculture of Atlantic salmon in marine net-pens by 2022.

Collaborative Marine Response Plans

NOAA Fisheries has developed an Oil Spill Emergency Response Plan for killer whales in partnership with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and the SeaDoc Society. In addition, the Canada–United States Joint Marine Pollution Contingency Plan, an agreement between the Canadian Coast Guard and the United States Coast Guard, provides a framework for Canada–U.S. cooperation in response to marine pollution incidents threatening coastal waters of both countries and for major incidents in one country where the assistance of the neighboring country is required. Other spill-response collaborative initiatives include the Salish Sea Shared Waters Forum held in 2018, 2019, and 2020 that were facilitated by the Pacific States/British Columbia Oil Spill Task Force. Other spill response activities in Canada and the United States are also occurring at the local government level.

Learn More

- Be Whale Wise (Regulations and guidance for keeping proper distance from whales.)

- Environment and Climate Change Canada - Reducing the Threat of Contaminants to Southern Resident Killer Whales/Contaminants Technical Working Group

- U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) - Killer Whales

- B.C. Cetacean Sightings Network (Wild Whales)

- Puget Sound Vital Signs - Orcas

- Center for Whale Research

- University of British Columbia Marine Mammal Research Unit (MMRU)

- NOAA’s Saving the Southern Residents Story Map

- Southern Resident Orca Task Force

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada's Marine Environmental Quality Initiative

- Marine Mammal Commission Southern Resident Killer Whale

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada 2020 Management Measures to Protect Southern Resident Killer Whales

- NOAA Oil Spill Response and Killer Whales

Six Things You Can Do To Help

- Get involved in efforts to protect and restore salmon habitat in your community. Chinook salmon are especially important to Resident killer whale populations in the Salish Sea.

- Killer whales are sensitive to noise and disturbance from boats. Consult Be Whale Wise before getting out on the water and follow the laws and guidelines in Washington and British Columbia waters. Give killer whales space and enjoy whale watching from land. Check out thewhaletrail.org for the best spots to see whales from shore.

- When boating, prevent contaminants from entering local waters by using sewage pump-out services and reducing grey water discharge. Reduce your driving whenever possible. Cars and trucks can release contaminants onto roadways that eventually end up into the Salish Sea when rainwater rinses the contaminants away. As well, vehicle exhaust contains airborne contaminants that can contribute to ocean acidification.

- Choose to eat sustainably-harvested salmon and other seafood to help protect wild fish populations. Check for a certification symbol on food packaging or menus, such as Ocean Wise Sustainable Seafood. When fishing, be aware of relevant local and national regulations that may restrict what species or amounts you can take.

- Keep plastics, medications and toxic chemicals out of our waterways. Do your part to dispose of unused medicine and chemicals properly. Never dump them into household toilets and sinks or outside where they can get into ditches or storm drains. Consult safe disposal of prescription drug programs in Canada or the Washington's Safe Medication Return Program for pharmaceutical take-back programs. And when possible, use non-toxic cleaning products. Most public wastewater treatment systems are not designed to remove medicines or household chemicals. See if your community has a household hazardous waste collection facility that will take your old or unused chemicals.

- Report your sightings of killer whales. In British Columbia waters, report your whale sightings to the BC Cetacean Sightings Network. Your reports are used to reduce ship strikes and contribute to Science. The Orca Network, located in Washington State, also maintains a database of sightings of Killer Whales sighted in the Salish Sea.

References

Below is a listing of references used in this report.

- Alava, J.J., P.S. Ross, and F.A. Gobas. 2016. Food web bioaccumulation model for resident killer whales from the northeastern Pacific Ocean as a tool for the derivation of PBDE-sediment quality guidelines. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 70(1): 155-168.

- Alonso, M.B., A. Azevedo, J.P.M. Torres, P.R. Dorneles, E. Eljarrat, D. Barcelo, J. Lailson-Brito Jr., and O. Malm. 2014. Anthropogenic (PBDE) and naturally-produced (MeO-PBDE) brominated compounds in cetaceans — A review. Science of the Total Environment 481: 619-634.

- Barrett-Lennard, L.G., J.K.B. Ford, K.A. Heise. 1996. The mixed blessing of echolocation: differences in sonar use by fish eating and mammal eating killer whales. Animal Behaviour 51: 553-565. https://www.zoology.ubc.ca/~barrett/documents/themixedblessingofecholocationAnimalBehaviour51.pdf.

- Bigg, M.A., I.B. MacAskie and G.M. Ellis. 1976. Abundance and movements of killer whales off eastern and southern Vancouver Island with comments on management. Arctic Biological Station. Ste. Anne de Bellevue, Quebec. http://ecoreserves.bc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/abundance_and_movements_of_killer_whales.pdf.

- Bigg, M.A. 1982. An assessment of Killer Whale (Orcinus orca) stocks off Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Report of the International Whaling Commission 32: 655-666.

- Bigg, M.A., G.M. Ellis, J.K.B. Ford, and K.C. Balcomb. 1987. Killer whales: a study of their identification, genealogy and natural history in British Columbia and Washington State. Nanaimo, B.C.: Phantom Press & Publishers Inc. ISBN 0920883001.

- Bigg, M. A., P. F. Olesiuk, G. M. Ellis, J. K. B. Ford, and K. C. Balcomb. 1990. Social organizations and genealogy of resident killer whales (Orcinus orca) in the coastal waters of British Columbia and Washington State. Report of the International Whaling Commission, Special Issue 12: 383- 405.

- CANUSPAC, 2017. Canada-United States Joint Marine Pollution Contingency Plan. Signed by Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans Coast Guard and US Department of Homeland Security Coast Guard. Washington, DC. https://www.rrt10nwac.com/files/Canadian CG - USCG Joint Marine Contingency Plan.pdf.

- Environment Canada and United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2014. Georgia Basin – Puget Sound Airshed Characterization Report, 2014. Vingarzan R., So R., Kotchenruther R., editors. Environment Canada, Pacific and Yukon Region, Vancouver (BC). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 10, Seattle (WA). ISBN 978-1-100-22695-8. Cat. No.: En84-3/2013E-PDF. EPA 910-R-14-002. http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/ec/En84-3-2013-eng.pdf.

- COSEWIC. 2008. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Killer Whale (Orcinus orca) Southern Resident population, Northern Resident population, West Coast Transient population, Offshore population and Northwest Atlantic / Eastern Arctic population in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa, ON. https://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/cosewic/sr_killer_whale_0809_e.pdf.

- Cullon, D.L., M.B. Yunker, C. Alleyne, N.J. Dangerfield, S. O’Neill, M.J. Whiticar and P.S. Ross. 2009. Persistent organic pollutants in chinook salmon (Onchorynchus tshawytischa): implications for resident killer whales of British Columbia and adjacent waters. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 28(1): 148-161.

- Dalheim, M., A. Schulman-Janiger, N. Black, R. Ternullo, D. Ellifrit, and K. Balcomb, 2008. Eastern Temperate North Pacific Offshore Killer Whales (Orcinus orca): Occurrence, Movements, and Insights into Feeding Ecology. Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce. 43. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub/43

- deBruyn, P.J.N., C.A. Tosh, and A. Terauds. 2013. Killer whale ecotypes: is there a global model? Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 88(1): 62-80.

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans. 2018. Recovery Strategy for the Northern and Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Ottawa, ON. 2nd Amendment. https://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/virtual_sara/files/plans/Rs-ResidentKillerWhale-v00-2018Aug-Eng.pdf.

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans. 2010. Chinook Salmon Abundance Levels and Survival of Resident Killer Whales. Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat. Pacific Region. Science Advisory Report 2009/075. http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Library/340360.pdf.

- Desforges, J-P, A. Hall, B. McConnell, A. Rosing-Asvid, J.L. Barber, A. Brownlow, S. De Guise, I. Eulaers, P.D. Jepson, R.J. Letcher, M. Levin, P.S. Ross, F. Samarra, G. Víkingson, C. Sonne, and R. Dietz. 2018. Predicting Global Killer Whale Population Collapse from PCB Pollution. Science 361(6409):1373–76. doi:10.1126/science.aat1953.

- Ford, M.J., J. Hempelmann, M.B. Hanson, K.L. Ayres, R.W. Baird, C.K. Simmons, J.I. Lundin, G.S. Schorr, S.K. Wasser, and L.K. Park. 2016. Estimation of a killer whale (Orcinus orca) population’s diet using sequencing analysis of DNA from feces. PLoS ONE 11(1): e0144956. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0144956&type=printable.

- Ford, J.F., G.M. Ellis, and K.C. Balcomb. 2000. Killer Whales, Second Edition: The natural history and genealogy of Orcinus orca in British Columbia and Washington. UBC Press, Vancouver and University of Washington Press, Seattle.

- Ford, J.K.B., B.M. Wright, G.M. Ellis and J.R. Candy. 2010. Chinook salmon predation by resident killer whales: seasonal and regional selectivity, stock identify of prey and consumption rates. DFO Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Research Document 2009/101.

- Garrett, C. and P.S. Ross. 2010. Recovering resident killer whales: a guide to contaminant sources, mitigation and regulations in British Columbia. Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2894. Vancouver, BC. http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/Library/341729.pdf.

- Hanson, M.B., R.W. Baird, J.K.B. Ford, J. Hempelmann-Halos, M.M. Van Doornik, J.R. Candy, C.K. Emmons, G.S. Schorr, B. Gisborne, K.L. Ayres, S.K. Wasser, K.C. Balcomb, K. Balcomb-Bartok, J.G. Sneva and M.J. Ford. 2010. Species and stock identification of prey consumed by endangered southern resident killer whales in their summer range. Endangered Species Research 11: 60-82. https://www.orcanetwork.org/Main/PDF/preystudy2010.pdf.

- Hickie, B.E., P.S. Ross, R.W. Macdonald and J.K.B. Ford. Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) face protracted health risks associated with lifetime exposure to PCBs. Environmental Science and Technology 2007(41): 6613-6619.

- Hilborn, R., S.P. Cox, F.M.D. Gulland, D.G. Hankin, N.T. Hobbs, D.E. Schindler, and A.W. Trites. 2012. The Effects of Salmon Fisheries on Southern Resident Killer Whales: Final Report of the Independent Science Panel. Prepared with the assistance of D.R. Marmorek and A.W. Hall, ESSA Technologies Ltd., Vancouver, B.C. for National Marine Fisheries Service (Seattle, WA) and Fisheries and Oceans Canada (Vancouver, B.C.). https://www.westcoast.fisheries.noaa.gov/publications/protected_species/marine_mammals/killer_whales/recovery/kw-effects_of_salmon_fisheries_on_srkw-final-rpt.pdf.

- Holt M.M., Noren D.P., Veirs V., Emmons C.K., and S. Veirs. 2009. Speaking up: killer whales (Orcinus orca) increase their call amplitude in response to vessel noise. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 125:EL27-EL31. https://doi.org/10.1121%2F1.3040028.

- Krahn, M.M., M.B. Hanson, R.W. Baird, R.H. Boyer, D.G. Burrows, C.K. Emmons, J.K.B. Ford, L.L. Jones, D.P.Noren, P.S. Ross, G.S. Schorr and T.K. Collier. 2007. Persistent organic pollutants and stable isotopes in biopsy samples (2004/2006) from Southern Resident Killer Whales. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 54(2007): 1903-1911.

- Krahn, M.M., M.J. Ford, W.F. Perrin, P.R. Wade, R.P. Angliss, M.B. Hanson, B.L. Taylor, G.M. Ylitalo, M.E. Dahlheim, J.E. Stein and R.S. Waples. 2004. 2004 Status review of southern resident killer whales (Orcinus orca) under the Endangered Species Act. U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NMFSC-62. https://www.nwfsc.noaa.gov/assets/25/6377_02102005_172234_krahnstatusrevtm62final.pdf.

- MacDuffee, M., A.R. Rosenberger, R. Dixon, A. Jarvela Rosenberger, C.H. Fox and P.C. Paquet. 2016. Our Threatened Coast: Nature and Shared Benefits in the Salish Sea. Raincoast Conservation Foundation. Sidney, British Columbia. Vers 1, pp. 108.

- Matkin, C.O., E.L. Saulitis, G.M. Ellis, P. Olesiuk and S.D. Rice. 2008. Ongoing population level impacts on killer whales Orcinus orca following the “Exxon Valdez” oil spill in Prince William Sound, Alaska. Marine Ecology Progress Series 356: 269-281. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ce34/439bc6795d17d1cdacf5d621e19171f75b99.pdf.

- Murray, C.C., Hannah, L.C., Doniol-Valcroze, T., Wright, B., Stredulinsky, E., Locke, A., Lacy, R. 2019. Cumulative Effects Assessment for Northern and Southern Resident Killer Whale Populations in the Northeast Pacific. DFO Can. Sci. Advisory. Sec. Res. Doc. 2019/056. x.+88p. http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/Publications/ResDocs-DocRech/2019/2019_056-eng.pdf.

- Nattrass, S. Croft, D.P., Ellis, S., Cant, M.A., Weiss, M.N., Wright, B.N., Stredulinsky, E., Doniol-Valcroze, T., Ford, J.K.B., Balcomb, K.C., Franks, D.W. 2019. Postreproductive killer whale grandmothers improve the survival of their grandoffspring. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Dec 2019, 116 (52) 26669-26673. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1903844116

- NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Agency). 2005. Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants: Endangered Status for Southern Resident Killer Whales. Federal Register. 70 FR 69903. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2005-11-18/pdf/05-22859.pdf.

- NOAA. 2006. Designation of Critical Habitat for Southern Resident Killer Whales. National Marine Fisheries Service: Northwest Region. https://www.westcoast.fisheries.noaa.gov/publications/protected_species/marine_mammals/killer_whales/esa_status/srkw-ch-bio-rpt.pdf.

- NOAA. 2008. Recovery Plan for Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca). National Marine Fisheries Service, Northwest Regional Office. Seattle, Washington. https://www.westcoast.fisheries.noaa.gov/publications/protected_species/marine_mammals/killer_whales/esa_status/srkw-recov-plan.pdf.

- NOAA. 2016. Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) Five Year Review: Summary and Evaluation. National Marine Fisheries Service, Northwest Regional Office. Seattle, Washington. https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/17031/noaa_17031_DS1.pdf.

- NOAA. 2014. Southern Resident Killer Whales: 10 Years of Research and Conservation. Northwest Fisheries Science Centre, West Coast Region. Accessed July 3, 2019. https://www.nwfsc.noaa.gov/news/features/killer_whale_report/pdfs/bigreport62514.pdf.

- O’Connor, S., Campbell, R., Cortez, H., Knowles, T. 2009. Whale Watching Worldwide: tourism numbers, expenditures and expanding economic beliefs, a special report from the International Fund for Animal Welfare, Yarmouth MA, USA, prepared by Economists at Large.

- Ogilvie, M.K.H. 2019. Phenological effects on Southern Resident Killer Whale Population Dynamics. M.Sc. Thesis, Royal Roads University.

- Parsons, J.M., K.C. Balcomb, J.K.B. Ford and J.W. Durban. 2009. The social dynamics of southern resident killer whales and conservation implications for this endangered population. Animal Behaviour 77(4): 963-971.

- Pacific Salmon Commission. 2019. Annual Report of Catch and Escapement for 2018. Report TCCHINOOK (19)-01.pdf. Joint Chinook Technical Committee Report. Accessed July 3, 2019. https://www.psc.org/download/35/chinook-technical-committee/11776/tcchinook-19-1.pdf.

- Rayne, S., M.G. Ikonomou, P.S. Ross, G.E. Ellis and L.G. Barrett-Lennard. 2004. PBDEs, PBBs and PCNs in three communities of free-ranging killer whales (Orcinus orca) from the Northeastern Pacific Ocean. Environmental Science and Technology 2004(38): 4293-4299.

- Shields, M.W., Hysong-Shimazu, S., Shields, J.C., Woodruff., J. 2018. Increased presence of mammal-eating killer whales in the Salish Sea with implications for predator-prey dynamics.” PeerJ 6:e6062 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6062.

- Shields M.W., Lindell J., Woodruff J. 2018.Declining spring usage of core habitat by endangered fish-eating killer whales reflects decreased availability of their primary prey. Pacific Conservation Biology 24, 189-193.

- Van Deren, M., J. Mojica, J. Martin, C. Armistead, and C. Koefod. 2019. The whales in our waters: the economic benefits of whale watching in San Juan County. Earth Economics. Tacoma, WA. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/561dcdc6e4b039470e9afc00/t/5c48a1e442bfc14525263268/1548264128844/SRKW_EarthEconomics_Jan2019-Digital.pdf.

- Ward, E.J., B.X. Semmens, E.E. Holmes and K.C. Balcomb. 2010. Effects of multiple levels of social organization on survival and abundance. Conservation Biology 25(2): 350-355.

- Wasser, S.K., J.I. Lundin, K. Ayres, E. Seely, D. Giles, K. Balcomb, J. Hempelmann, K. Parsons, and R. Booth. 2017. Population growth is limited by nutritional impacts on pregnancy success in endangered Southern Resident killer whales (Orcinus orca). PLoS ONE 12(6): e0179824. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0179824&type=printable.

- Williams, R., D.E. Bain, J.C. Smith and D. Lusseau. 2009. Effects of vessels on behaviour patterns of individual southern resident killer whales Orcinus orca. Endangered Species Research 6: 199-209. https://www.int-res.com/articles/esr2008/6/n006p199.pdf.