Shellfish Harvesting

Updated June 2021 based on data available through December 2019.

- About Shellfish Harvesting

- What's Happening?

- Why Is It Important?

- Why Is It Happening?

- What's Being Done About It?

- Five Things You Can Do To Help

- References

About Shellfish Harvesting

The Salish Sea is one of the leading producers of shellfish in North America, and commercial product is shipped around the world. Hundreds of miles of Puget Sound and Georgia Basin shorelines and beaches also attract hundreds of thousands of recreational harvesters each year.

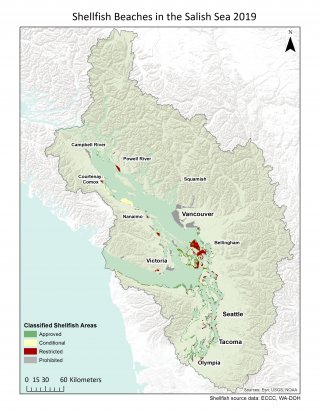

This shellfish harvesting indicator reflects access to safe shellfish resources in the Salish Sea ecosystem. Shellfish beaches are assigned a classification that determines whether shellfish in that area are safe to eat. The classification is based on the results of a local sanitary survey, marine water quality monitoring and local shoreline survey.

Because they feed by filtering the water that washes over the shellfish bed, they can accumulate disease-causing bacteria and viruses that are harmful to people. The Washington State Department of Health (for Puget Sound) and the Canadian Shellfish Sanitation Program (for Georgia Basin) test shellfish and the water where they grow to make sure the shellfish are safe to eat.

If monitoring shows poor water quality, or if the sanitary survey identifies potential impacts to water quality, then the shellfish beach may be closed to harvesting. Examples of potential impacts to water quality that commonly close shellfish beaches include marinas and outfall pipes, which may carry contaminated wastewater or runoff from urban areas, and also failing septic systems and agricultural runoff.

If there is a lack of marine water quality monitoring and a request for commercial shellfish harvesting, then the area may be designated as restricted and additional assurances would be needed for harvest, such as relaying to clean waters for a time prior to harvest.

For more information about monitoring of shellfish areas, see Washington Department of Health Shellfish Growing Areas and Canada's Shellfish Sanitation Program Manual.

Shellfish Beach Classifications

- Approved: This classification applies to areas that are safe for harvesting based on the sanitary survey. This classification authorizes commercial shellfish harvest for direct marketing.

- Conditionally Approved: This classification means an area is safe for harvesting except during certain periods. The length of the closed periods is based on water sample data that show how long it takes for safe harvesting conditions to return to that area.

- Restricted: When marine water quality monitoring is not available for the area or if the sanitary survey shows a limited degree of pollution, including from non-human sources, the area may be classified as restricted. Shellfish harvested commercially from restricted growing areas cannot be marketed directly. They must be transplanted to approved growing areas for a specified amount of time, allowing shellfish to naturally cleanse themselves of any contaminants before they are harvested for market.

- Prohibited: This classification applies to growing areas near sewage treatment plant and industrial outfalls, marinas, and other pollution sources. Commercial shellfish harvests are not allowed from prohibited areas.

Marine water quality samples are collected throughout the year to support shellfish bed classifications. Shoreline surveys are conducted less frequently, but each year dozens of shellfish growing areas are surveyed to evaluate all potential sources of pollution that may impact water quality in that area.

In Puget Sound, many restricted areas have been classified where monitoring data is not available, notably in the San Juan Islands (see map above). Shellfish from these specific restricted areas can be transferred to a known and monitored location for a period of time in order to remove any contamination concerns and allow for marketing and consumption.

For detailed interactive maps of shellfish harvesting areas, visit:

Sustainable Perspective

Early Salish villages relied on large quantities of clams, oysters and crabs. The history and evidence of such abundant use has been established through the great shell mounds - called middens - still found today near ancient village sites. One midden near Everett in the Snohomish River delta was found to be almost six feet in height and nearly a quarter mile long.

Today, Coast Salish tribes still rely on shellfish in addition to salmon as a source of high protein, low fat, nutrient rich foods that comprise a large portion of the traditional diet. Since clams are sedentary, they provide a stable food source - more reliable than hunting or fishing. A saying shared by many Coast Salish tribes is that, "when the tide is out, the table is set."

Sources: Donatuto, 2009; Dong, 2001; Kruckeberg, 1991

Clam Gardens

Based on a visit to a clam garden in British Columbia, the Swinomish Tribe is reviving an ancient mariculture practice by installing a clam garden on reservation tidelands to address goals identified in the Swinomish Climate Adaptation Plan.

Clam gardens are intertidal features modified by Northwest Coastal Indigenous people (e.g., moving and clearing rocks, building rock walls to stabilize sediment upshore, creating terraces in the tide flats to alter beach slope and substrate) to enhance clam habitat for optimal shellfish production. Using clam gardens to promote robust native clam populations will encourage the integration of traditional ecological knowledge in contemporary resource management and climate change adaptation strategies as well as bolster local food security, support tribal treaty rights, and provide ecological and cultural benefits to the community.

Learn more about the Swinomish community's visit to the clam garden (YouTube).

What's Happening?

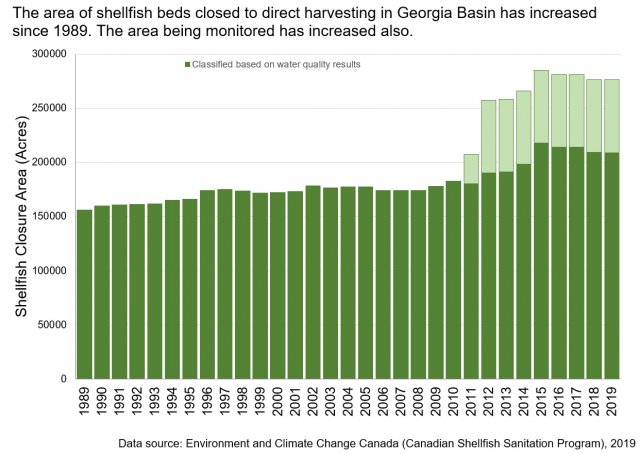

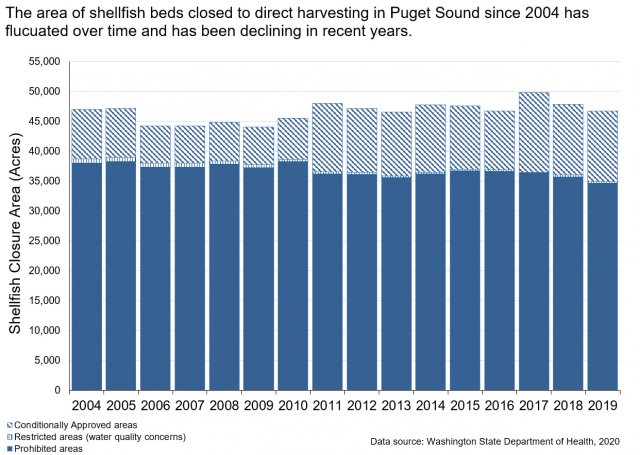

In 2018, over 275,000 acres (about 1,110 km2) of shellfish beds were closed to harvesting in the Georgia Basin, and almost 47,000 acres (about 190 km2) in Puget Sound were prohibited or had conditional harvest. These values include all areas that are prohibited or have only conditional approval for commercial harvest.

Georgia Basin

Since 1989 in the Georgia Basin, the area of tidal lands closed to shellfish harvesting has steadily increased by 44% (see chart below). However, this is partly due to increased monitoring efforts and refinements in designating closure areas. The measurement of shellfish classified areas in the Georgia Basin became more precise with the development of better geographic information systems that added the ability to track permanent and automatic prohibited areas that are described by section 4.1.3.5 of the Canadian Shellfish Sanitation Program manual.

The classification practices in shellfish areas have also changed over time to address emerging health issues. In Canada, new health-risk advice was developed and adopted for shellfish areas impacted by wastewater treatment outfalls. This advice was based on research on the persistence of viruses in sewage. In the Georgia Basin, the size of areas that were automatically prohibited from any shellfish harvest were increased around the several wastewater systems in 2012. Increased prohibited zones were put in place to maximize the protection of shellfish consumers while detailed investigations of each large wastewater system were planned and completed.

Puget Sound

In 2004, in Puget Sound, the area of tidal lands closed (i.e. prohibited) to shellfish harvesting was about 38,000 acres (or about 154,000 km2). In 2019, the area of closed beds had decreased to about 35,000 acres (142 km2). Puget Sound also monitors other conditionally-approved areas that are available for harvest if the conditions are suitable. The amount of acreage classified as conditionally-approved in Puget Sound has been steadily increasing since 2004.

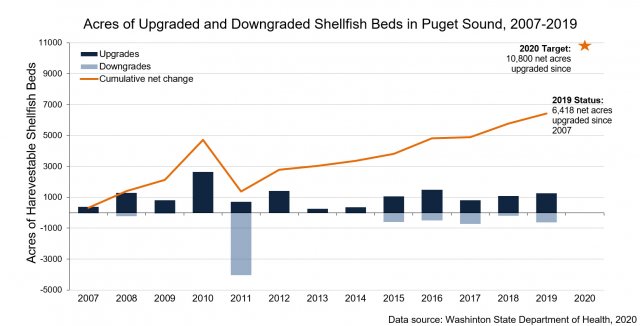

This is a result of local prohibited classifications being upgraded to conditionally approved status; conditionally approved designations being upgraded to approved status; and less frequently, some local downgrades from conditionally approved to prohibited status. However, overall, there has been a trend toward improvement, particularly since 2007 (see chart below) with an overall net gain of some 6,400 acres since 2007 (see net change chart further below).

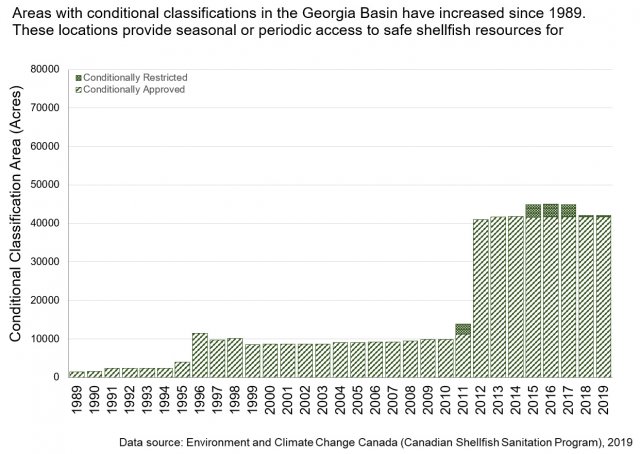

Conditional Shellfish Areas Help Manage Shellfish Beds Safely

Conditional shellfish areas in both the Georgia Basin and Puget Sound are also important to harvesters. Conditionally approved areas are routinely monitored and provide access to shellfish resources when it is known to be safe, such as during dry periods. Some restricted and conditionally-restricted areas are managed to allow access to shellfish that can be decontaminated.

In the Georgia Basin, there has been an overall increase in conditionally-classified areas. These areas allow for shellfish bed access only during safe conditions and provide greater access to shellfish resources for commercial and recreational harvesters.

Why Is It Important?

The Salish Sea region is one of the largest producers of shellfish in North America. Areas that are closed to shellfish harvesting can impact the livelihood of growers, workers, supermarkets, restaurants, hotels, and sales of recreational equipment, among other economic losses. Shellfish closures also impact First Nation and tribal shellfish harvesting rights, which have been part of their traditions and economies for thousands of years.

Shellfish are an important part of the economy, lifestyle and heritage of this region. The Salish Sea is home to an abundance of clams, mussels, oysters, crab and shrimp. Each acre of commercial Pacific oyster beds produces an overall value between $10,000 and $20,000 per year. Overall, shellfish harvest contributes roughly $180 million to Washington’s economy per year, and 3,200 direct and indirect jobs.

Non-tribal commercial shellfish landings from Puget Sound in 2006 were valued at about $15 million dollars per year in ex-vessel value for harvesters (i.e., the price received by commercial fishers for fish landed at the dock). The processing income more than doubles this value – and this valuation is now fifteen years old.

Recreation is another important economic factor associated with shellfish harvesting, with over a hundred thousand licensed harvesters, half a million harvest days, and a net economic value of over $20 million dollars per year. Also, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife collects about $1.5 million annually in licensing fees for harvest of shellfish and seaweed.

Shellfish also help improve water clarity by filtering the water, provide food for animals higher in the food webs, and support eelgrass growth, which provides a crucial nursery for many fish and other marine animals.

Why Is It Happening?

The primary sources of pollution that lead to closure of shellfish harvesting areas are polluted runoff from urban areas and farms, and uncontrolled sources of sewage and septic wastes.

Urbanization creates more roads and other impervious surfaces that can quickly transport oil, grease, chemicals, fertilizers, pet waste, sediment and other pollution when it rains. Likewise, manure and agricultural chemicals that are not properly treated or controlled by farms can end up in our waterways and impact shellfish growing areas.

Sewage from malfunctioning or aging treatment plants and failure of home septic systems can release human waste and other dangerous bacteria and pathogens into shellfish-growing areas. Some marinas and boaters also release untreated sewage to water.

Puget Sound

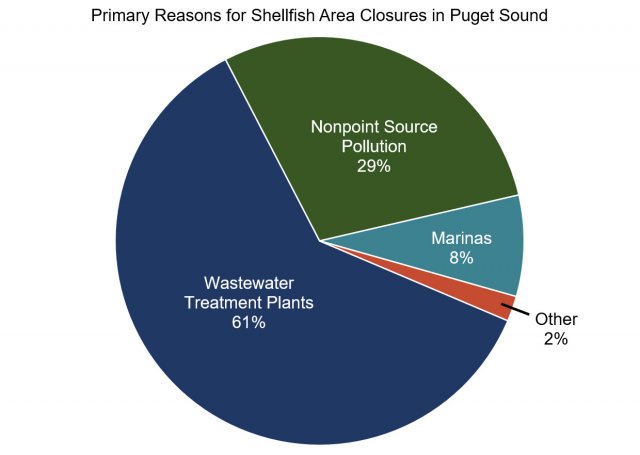

The chart below shows why shellfish beaches in Puget Sound were classified as prohibited for harvesting in 2018:

- 61% were near wastewater treatment plant outfalls. Note: Most prohibited areas around wastewater outfalls are based on the potential for pollution and not actual water quality.

- 29% were impacted or potentially impacted by nonpoint pollution sources such as poorly functioning on-site sewage systems (septic), farms, wildlife, and other potential sources.

- 8% were near marinas. Note: Prohibited areas around marinas are based on the number of boats and their potential to contribute pollution, not actual water quality.

- 2% were prohibited based on other sources.

Georgia Basin

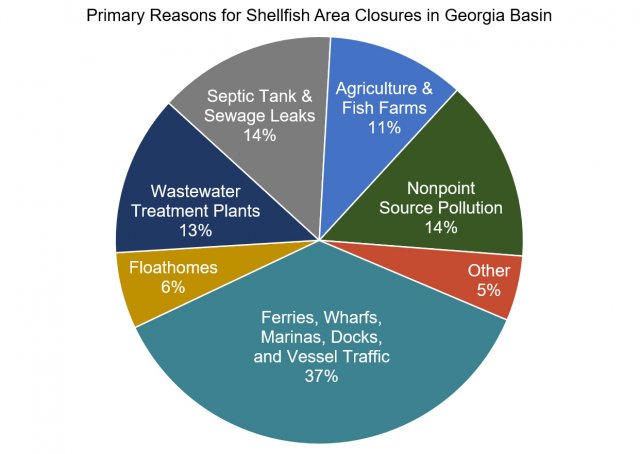

In contrast, the primary reason for the closure of shellfish beds in Georgia Basin was proximity to ferry terminals, wharfs, marinas, docks, or other vessel traffic, which contributed to 37% of the shellfish closure areas. Impacts from wastewater treatment plant outfalls, sewage and septic leaks and overflows, agriculture and fish farms, and other nonpoint source pollution were about equal (11-14% each). Shellfish beds were also closed 6% of the time due to the presence of float homes, and 5% of the time for other reasons.

What's Being Done About It?

Government agencies are working with communities to create shellfish protection districts and develop strategies for both preventing and responding to harvest closures. Tribes in Washington and First Nations in British Columbia are leading community partnerships that target specific pollution sources. In both the U.S.A. and Canada, many shellfish growers belong to trade associations which foster environmental responsibility and effective stewardship of shellfish growing areas.

Puget Sound

The Puget Sound Partnership has set a target to upgrade 10,800 total net acres (44 km2) in Puget Sound between 2007 and 2020.

As of 2019, the area of upgraded shellfish beaches in Puget Sound had increased by 6,418 net acres, which is 64% of the 2020 target (see chart below).

The Washington Department of Health (under the U.S. National Shellfish Sanitation Program) also conducts sanitary surveys in shellfish growing areas and closes harvest areas when there is a threat to public health. These surveys include a shoreline evaluation to identify pollution sources that may impact water quality, sampling to determine bacteria levels in the water, weather conditions, tides and other factors that may affect the distribution of pollution in the area.

Georgia Basin

In the Georgia Basin, the Canadian Shellfish Sanitation Program mandates a partnership in which Fisheries and Oceans Canada opens and closes shellfish areas on the recommendation of either Environment and Climate Change Canada or the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). CFIA maintains the biotoxin surveillance program and monitors the processing of edible shellfish for compliance with federal standards.

Environment and Climate Change Canada monitors the level of fecal contamination in shellfish growing areas, identifies nearby pollution sources that could impact these areas, and recommends growing water classifications for approval by the Pacific Region Interdepartmental Shellfish Committee.

In 2012, new Wastewater System Effluent Regulations came into force in Canada that will reduce pollution from wastewater treatment plants over time and lead to improved water quality to help reduce shellfish beach closures. The new regulations required upgrades to secondary wastewater treatment at two facilities in Metro Vancouver, including the Lions Gate Wastewater Treatment Plant in North Vancouver, and the Iona Island Wastewater Treatment Plant in Richmond. The cost of upgrades is estimated at $1.4 billion. The governments of Canada, British Columbia, and the Capital Regional District also recently announced a new wastewater treatment system for Greater Victoria with an estimated total capital cost of $782.7 million.

Success Stories

Drayton Harbor - Blaine, Washington

The downgrade of Drayton’s shellfish beds in 1997 sparked a community-wide effort to reduce pollution and clean up the harbor. Two decades later, the community efforts paid off. In November 2016, 810 acres of shellfish beds were reclassified as “approved” for harvest. Year-round harvests resumed for the first time in 22 years. In October, 2019 another 765 acres were reclassified from Prohibited to Approved.

Action in Drayton Harbor required a multi-faceted approach. A key first step was establishing a Pollution Identification and Correction (PIC) program. In Drayton, investigators with the PIC program located hot spots with a large concentration of fecal bacteria. They then worked upstream to identify potential sources. Clean-up targeted two major pollution sources: human waste and animal waste.

To address human waste, broken sewer lines and failing septic systems were repaired. Pump-out facilities were relocated to reduce the risk of spills from boats. A new sewage treatment plant was built and stormwater was separated from sewage collection.

To address waste from agriculture, the local conservation district helped farmers voluntarily improve their manure-handling practices. This included an end to the practice of applying liquid manure during shellfish harvesting season. New pet waste stations were installed in parks to prevent pet waste from washing into the harbor. Fish processors improved their management practices and reduced effluent.

Restoration of Drayton Harbor succeeded thanks to an intensive community effort that convened 30 partners to find and address pollution sources. Partners included key state and federal agencies, local government, conservation districts, and community groups and individual land-owners. Partners invested more than $2.8 million to restore water quality and dedicated over 38,000 volunteer hours.

Drayton Harbor is a living success story, but that doesn’t mean the work is done. To sustain the benefits of our recovery investments, the community must continue to address ongoing needs. National Estuary Program (NEP) funding leveraged local expertise and capital investment through both the Washington State Department of Health - through their NEP Strategic Initiative Lead role - and the many local health jurisdictions that they work with. This funding made it possible to develop a local, self-sustaining approach to reduce fecal contamination by helping individual property owners to pay for repairs. This funding also helped to create systems for pollution monitoring and community engagement. Continued support is needed, especially in areas where pollution risk is the greatest or where pollution sources are still unknown.

Learn more about the Washington Shellfish Initiative.

Samish Bay - Edison, Washington

In 2011, about 4,000 acres of the Samish Bay shellfish growing area was downgraded due to high bacteria levels in the Samish River. The Puget Sound Partnership, Washington State Department of Health, and local health districts responded by teaming up with the Clean Samish Initiative and others to develop a ten-point action plan to direct cleanup in the upstream watersheds.

Actions included increased inspections and maintenance of septic systems, more education of dairy and other landowners, assistance to farmers for livestock fencing and to landowners for portable restrooms for recreational users. Their goal is to control local sources of pollution and re-open these valuable harvesting areas.

EPA supports the Skagit County Pollution Identification and Correction (PIC) Program and the Clean Samish Initiative to improve water quality in Samish Bay - a large and highly valued 4,000 acre commercial shellfish growing area. Skagit County uses unique methods - including a sewage sniffing dog - to find and fix sources of fecal pollution, and EPA’s Manchester Laboratory is partnering with the county to perform microbial source tracking analysis to help narrow down which animals are contributing to fecal contamination trouble spots.

All this work is making a difference:

- Bacteria levels in the Samish River watershed have been reduced by 60 percent since 2011.

- Bay View State Park's swim beach, which was closed for one-third of the swimming season due to bacterial pollution in 2015, was open all of summer 2019.

- The number of days that commercial shellfish beds are closed in spring due to pollution has been reduced by 60 percent since 2014.

Learn more about the Clean Samish Initiative.

Indian Arm - Vancouver, B.C.

All of Burrard Inlet, including Indian Arm and Port Moody Arm, have been prohibited to direct shellfish harvesting since the 1980s due to the intensity of urban and industrial activity.

In May 2016, however, area 28-13 or Croker Island, toward the northern tip of Indian Arm Provincial Park near Granite Falls, was re-classified (opened) for limited harvest for food, social, and ceremonial purposes by the Tsleil-Waututh Nation.

This followed a request in 2006 to examine this remote portion of Indian Arm on its own merit, and through 10 years of collaboration with Canadian federal departments, including Environment and Climate Change Canada, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, and Health Canada the effort was successful.

Cooperative efforts included interviews with elders for historic knowledge on harvest areas, marine water quality monitoring for fecal contamination, biotoxin testing, ongoing shoreline evaluations to assess actual and potential sources of fecal contamination, a health risk assessment, and the development of a community harvest plan.

The first shellfish harvest in over 30 years took place in October 2016. Water quality monitoring has continued in the area since then and community harvesting opportunities continued in 2017, 2018, and 2019.

Learn More

Learn more about some of the work our partners are doing to protect shellfish:

- Washington Dept. of Health - Shellfish

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration National Shellfish Sanitation Program

- Canadian Shellfish Sanitation Program

- Puget Sound Partnership Vital Signs - Shellfish Beds

- MetroVancouver Integrated Liquid Waste and Resource Management Plan

- Capital Regional District Wastewater Treatment Project (Vancouver Island and Gulf Islands)

Five Things You Can Do To Help

- Scoop your pet's poop. Pet waste is full of bacteria that can get washed into waterways and make people sick if they eat contaminated shellfish. Bag it and place it in the trash.

- If you're a boater, manage your sewage wastes properly. Do not discharge treated or untreated sewage into our waterways. Many marinas provide sewage pump out as a free or low cost service.

- If your home or business uses a septic system, take time to learn how your septic system works and keep it properly maintained. Ask for maintenance advice from your local health agency.

- Use techniques such as natural landscaping, rain gardens, rain barrels, green roofs and permeable paving to help reduce the need for chemical fertilizers and reduce runoff into ditches and storm drains.

- Do your part to dispose of unused medicine and chemicals properly. Never dump into household toilets and sinks or outside where they can get into ditches or storm drains. See if your community has a household hazardous waste drop-off facility that will take your old or unused chemicals.

References

Below is a listing of references used in this report.

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency. 2019. Canadian Shellfish Sanitation Program. Accessed August 26, 2019. https://inspection.canada.ca/preventive-controls/fish/cssp/eng/1563470078092/1563470123546.

- US Food and Drug Administration. 2017. National Shellfish Sanitation Program: Guide for the Control of Molluscan Shellfish. https://www.fda.gov/media/117080/download.

- Donatuto, J. 2009. White Paper: Key Indicators of Tribal Human Health in Relation to the Salish Sea. https://swinomish-nsn.gov/media/53954/swin_cr_2009_01.pdf.

- Dong, F.M. 2001. The nutritional value of shellfish. Washington Sea Grant: WSG-MR 09-03. U.S. Natl. Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, pp 4-8.

- Kruckeberg, A.R. 1991. The history of Puget Sound Country. University of Washington Press, Seattle, WA.

- Dethier, M. 2006. Native Shellfish in Nearshore Ecosystems of Puget Sound. Puget Sound Nearshore Partnership Report No. 2006-04. Published by Seattle District, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle, Washington

- TCW Economics. 2008. Economic analysis of the non-treaty commercial and recreational fisheries in Washington State. December 2008. Sacramento, CA. With technical assistance from The Research Group, Corvallis, OR.

- Washington State Sport Catch Report for 2015; 2017 by Eric Kraig and Tracey Scalici, Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife.