Chinook Salmon

Updated June 2021 based on data available through December 2017.

- About Chinook Salmon

- What's Happening?

- Why Is It Important?

- Why Is It Happening?

- What's Being Done About It?

- Five Things You Can Do To Help

- References

About Chinook Salmon

Salmon are an iconic species of the Salish Sea. They play a critical role in supporting and maintaining ecological health, and in the social fabric of First Nations and tribal culture.

Strong commercial and recreational salmon fisheries also make salmon an important economic engine for the region.

Chinook (Onchorhychus tshawytscha) are the largest salmon, and are commonly known as "Kings" or "Tyee" (which means "chief" in Chinook jargon).

Ecology and Life History

The Salish Sea is home to nine different species of salmon and trout:

- Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha).

- Coho salmon (also called silver salmon; Oncorhynchus kisutch).

- Chum salmon (also called dog salmon; Oncorhynchus keta).

- Sockeye salmon (also called red salmon; Oncorhynchus nerka).

- Pink salmon (also called humpback salmon; Oncorhynchus gorbuscha).

- Steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss).

- Cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii).

- Bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus).

- Dolly Varden trout (Salvelinus malma).

Chinook are a particularly important species in the Salish Sea ecosystem because of both their economic and ecological value.

Chinook salmon are born in fresh water, spend much of their life at sea, and then return to fresh water to spawn (this is called anadromous). They die after spawning once (this is called semelparous). Chinook vary from other salmonids in their age at seaward migration, length of residence in freshwater, estuaries and the ocean, distribution and migration in the ocean, and the age, season and length of migration for spawning.

Distinguished by small black spots on both lobes of their tail fin, and black gums in their lower jaw, they are the largest of the salmonids in size – averaging 15 pounds in commercial marine fisheries, 30 pounds in sport marine fisheries and reaching over 75 pounds on the spawning grounds of some populations. Chinook salmon have the longest migration routes from early emergence from their spawning redds (spawning nests) in higher elevation streams and rivers, down long river corridors and then out into the Pacific gyre for years only to return thousands of miles up their same natal rivers to their original spawning areas.

Sustainable Perspectives

First foods ceremonies are one way Coast Salish communities celebrate respect for the earth. In spring, families celebrate the first Chinook salmon caught with First Salmon ceremonies called Thehitem ("looking after the fish.") At the end of the ceremonies the bones of the salmon are returned to the river with a prayer giving thanks to the Creator, Chíchelh Siyá:m, and the salmon people. This is to show that the salmon were well-treated and welcome the following year.

Traditional Names for Chinook Salmon

- Blackmouth (USA)

- K'with'thet (Salish)

- K'wolexw (Salish)

- King salmon (USA, Canada)

- Oncorhynchus tshawytscha (Latin)

- Sa aeup (Nuuchahnulth)

- Sa-cin (Nuuchahnulth)

- Schaanexw (Salish)

- Shamet skelex (Salish)

- Shmexwalsh (Salish)

- Sinaech (Salish)

- Sk'wel'eng's schaanexw (Salish)

- Slhop' schaanexw (Salish)

- Spak'ws schaanexw (Salish)

- Spring salmon (USA, Canada, Australia)

- St'thokwi (Salish)

- Su-ha (Nuuchahnulth)

- Tyee salmon (Canada, USA)

What's Happening?

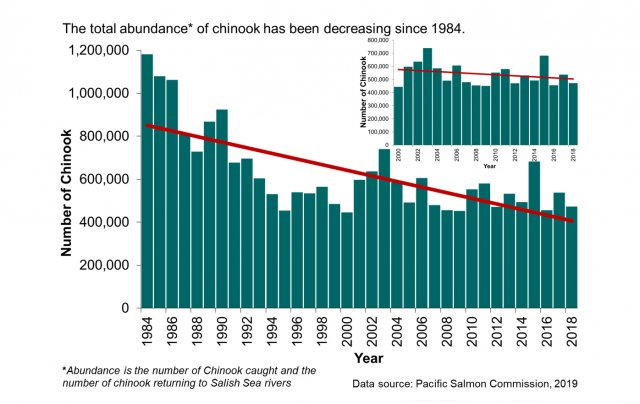

Just over 473,000 adult Chinook salmon were estimated by the Pacific Salmon Commission to have passed through the Salish Sea in 2018 (see charts below). This is a 60% reduction in Chinook salmon abundance since the Commission began tracking salmon data in 1984. The current estimate does not include the effect of predators or other sources of Chinook mortality before spawning, so it may overestimate the spawning population size.

Between 2000 and 2018, the total number of Chinook returning to the Salish Sea has shown a relatively stable trend. During this time period, the technical reports also show a small increase in catch and a small decrease in returning spawners, particularly over the last few reporting years.

There has been inter-annual variability in population size since tracking Chinook populations began. Currently for most stocks of Salish Sea Chinook salmon that are monitored by the Pacific Salmon Commission, about the same number of fish return each year to spawn. A few individual stocks have shown recent changes in spawning fish returns, with some stocks showing increases in returning spawner numbers while other stocks have decreasing numbers of returning fish. Research completed in 2018 has suggested that the average age and size of returning Chinook salmon is changing too, with fish maturing and spawning at younger ages. The largest-sized Chinook salmon are less common now compared to 40 years ago.

Taken together, all the monitoring data suggest that no improvement in the overall trend of Chinook salmon abundance has happened since 1999, when Puget Sound Chinook salmon were listed as a threatened species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

Puget Sound Chinook salmon have not improved according to the 2020 Puget Sound Vital Signs indicator chart for Chinook salmon.

Puget Sound was once home to larger populations of Chinook and other salmon, with a greater diversity of traits than populations existing today. Only 22 of at least 37 historic Chinook salmon populations remain in this ecosystem. The remaining Chinook salmon populations are at as little as 10% of their historic numbers. The decline in salmon is closely associated with harvest rates, decline in the overall health of the Salish Sea and its contributing watersheds, habitat loss, and/or the lowered resilience of these ecosystems to climate change.

The importance of salmon to coastal First Nations and tribes is evident in every coastal archaeological dig in the Salish Sea ecosystem, dating back thousands of years. Salmon have long been a constant and reliable part of the Coast Salish diet and cultural heritage. Reports suggest that harvest rates by the tribes were not enough to depress salmon populations, but rather, that their fishing practices amplified salmon abundance.

Why Is It Important?

Salmon provide food and support broader food-webs for a variety of wildlife, from bald eagles to killer whales to bears, and are a culturally invaluable food source for Puget Sound Tribes, First Nations, and our community as a whole. Chinook salmon in particular are the primary food source of the endangered Southern Resident Killer Whales (SRKWs). Because salmon die after spawning, their carcasses also provide abundant food and nutrients to plants and animals, including tiny aquatic insects and other invertebrates that in turn provide food for other animals.

During their life cycle, salmon transfer energy and nutrients between the Pacific Ocean and freshwater and land habitats. Since Chinook are the largest salmonid, they contribute the largest amount of biomass (organic matter) per fish to the ecosystem. In fact, in areas that have experienced dramatic declines in salmon, there is a measurable deficit of nutrients to help support the ecosystem.

Economic Impact

Commercial and recreational salmon fisheries in the U.S. state and Canadian province bordering the Salish Sea were worth an average of $1.1 billion annually (GDP) from 2012 to 2015. From 2012 to 2015, this value ranged from $12.6 to $31.5 million (see chart below).

Annual employment in commercial fishing industry is highly seasonal. In British Columbia (B.C.), full-time equivalent (FTE) employment related to commercial salmon fishing was estimated at 2,710 jobs in 2015. FTE employment related to recreational salmon fishing in B.C. was estimated at 6,480 jobs in the same year. In Washington State, FTE employment related to salmon fishing was 2,700 commercial fishing jobs and 3,540 recreational fishing jobs in 2015. The amount of FTE jobs supported by salmon fishing in the Salish Sea region has declined over time with declining salmon populations.

Both commercial and recreational salmon fisheries in the Salish Sea region are highly valued economically. In B.C., all salmon fisheries generated an average of $641 million annually in GDP from 2012 to 2015. In Washington State, all salmon fisheries generated an average of $477 million GDP annually during the same years.

Why Is It Happening?

The steep historical decline in Chinook salmon is associated with four main factors:

- Habitat loss and degradation.

- Harvest rates.

- Hatchery influence.

- Dams that impede migrations.

Additional factors increasingly recognized as contributing to declining salmon populations include climate change, ocean conditions, and marine mammal interactions.

Habitat Loss and Degradation

Since Chinook salmon habitat spans such a large area - from freshwater to the open ocean - they are more likely to be impacted by changes in habitat that supports a key life cycle. Such changes have been particularly prominent in freshwater habitats as the condition of streams, rivers, lakes and wetlands have been lost or highly degraded through timber harvest, agricultural practices, urbanization, and stormwater pollution that has impacted both the quality and quantity of salmon habitats.

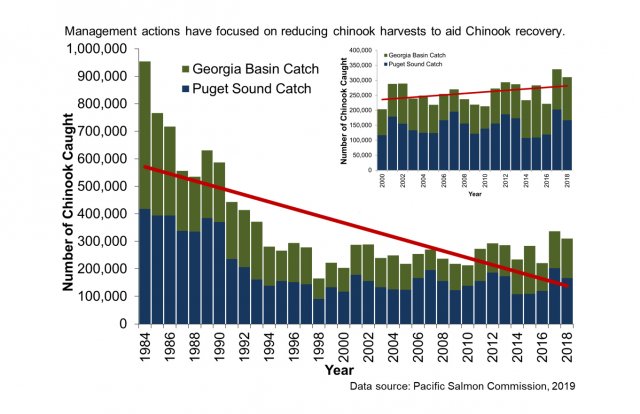

Harvest Rates

Between 1975 and 2018, almost 22 million Chinook were harvested for commercial, sport, or subsistence and ceremonial fisheries. It is difficult to estimate sustainable harvest limits. Harvest rates have remained relatively constant throughout the past decade and harvest rates are drastically lower now prior to the 1990s. This has caused hardship for U.S tribes and First Nations and caused decreased opportunities for both recreational and commercial fishing.

Hatchery Influence

One of the objectives of hatcheries is to preserve remaining depleted salmon populations by raising and then releasing extra Chinook salmon smolts into the wild. However, hatchery salmon can have negative impacts on wild salmon populations, including loss of natural population identity, diminished adaptability, and interference with natural salmon population recovery. Nevertheless, salmon are critical for the livelihoods and cultural identities of the many Coast Salish tribes, and over three quarters of salmon returning to the Puget Sound to spawn came from hatcheries. The increased production of Chinook salmon by hatcheries over the years has allowed the tribes and Southern Resident Killer Whales to continue using them as a food source and has prevented a more devastating population decline of the salmon overall.

Water Infrastructure Impeding Migrations

The control of streams and rivers using infrastructure like culverts, dams, or floodgates can impact all salmonid species, including Chinook populations. This is an issue throughout the Pacific Northwest, including the Salish Sea. Water infrastructure can result in migration passage barriers, water quality impairments, loss of habitat and hydrological changes. For example, in the lower Fraser River, use of floodgates can affect the complexity of upstream habitats and fish communities and the abundance of juvenile salmon populations. In the State of Washington, despite investing billions of dollars on various fish passage structures to direct fish migration around dams in Chinook-bearing rivers, Chinook salmon are still declining overall. Removing key dams in parts of Washington has been proposed as an option to restore Chinook salmon populations in some parts of Washington State.

Climate Change

Forecasted impacts from climate change on Chinook salmon include habitat changes, such as increased winter flooding, decreased summer and fall stream flows, and increased temperatures in streams and estuaries. Even small shifts in water temperature could alter the timing of migration, reduce growth, reduce availability of oxygen in the water, reduce availability of preferred food sources, and increase the susceptibility to toxins, parasites and disease.

Ocean Conditions

Salmon survival during their first few months at sea is linked to ocean conditions such as surface water temperature and salinity (saltiness), particularly in coastal and estuarine environments. Ocean conditions can also affect food supplies, numbers of predators, and migratory patterns for Chinook salmon. Each of these factors affects marine survival of Chinook and their ability to return to their streams to spawn.

Marine Mammal Interactions

Fewer Chinook salmon means that predators that eat salmon may be having a greater overall impact on the remaining populations of Chinook. California sea lions (Zalophus californianus), Pacific harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) and killer whales (Orcinus orca) are known to prey on Chinook in the Salish Sea. Since the mid-1970s, there has been an increase in the seasonal abundance of sea lions and in the year-round abundance of harbor seals. The number of Southern Resident Killer Whales (SRKWs) has decreased and Chinook salmon are their preferred food source over other salmonid species. The loss of Chinook abundance is likely a factor in the decreased abundance of SRKWs.

What's Being Done About It?

U.S. Treaties signed in the 1850s granted tribes "the right of taking fish from all usual and accustomed grounds and stations… in common with all citizens." The 1974 Supreme Court ruling, known as the Boldt Decision, re-affirmed the tribes' treaty reserved fishing rights. Today, the tribes and Washington State co-manage salmon recovery and habitat protection. In Puget Sound, the Partnership works with the tribes to achieve our shared goals to recover salmon.

The 1985 Pacific Salmon Treaty helped bring a science-based approach to international salmon conservation and harvest sharing.

In 1999, Puget Sound Chinook were listed for protection under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA), along with several other evolutionarily significant units (ESU) of Pacific salmon. In 2000, the National Marine Fisheries Service issued the salmon ESA 4(d) Rule, establishing take prohibitions for the Puget Sound Chinook and 13 other geographically-based Evolutionary Significant Units (ESU’s) of Chinook.

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) is the group responsible for determining the extinction risk of wildlife populations in Canada. It maintains a list of wildlife populations according to their biological vulnerability status. COSEWIC makes recommendations to the Canadian government for updating the official Species At Risk Act (SARA) legal list that provides protection for vulnerable populations.

In 2018, COSEWIC assessed Chinook salmon in southern British Columbia, which includes Salish Sea populations. Only 16 Chinook salmon populations with low or no influence from hatcheries were investigated at the time. COSEWIC will examine hatchery-supported populations in a separate investigation.

The results of the COSEWIC assessment found that only one Southern BC Chinook salmon designatable unit (which is a unit comparable to ESAs from the United States) had no risk of extinction. Two Chinook salmon designatable units (DUs) did not have enough data to assess properly. The remaining 13 Chinook salmon DUs were identified by COSEWIC as Endangered (8 DUs), Threatened (4 DUs) and Special Concern (1 DU). The Canadian process for listing these Southern BC Chinook salmon DUs on SARA is underway and engagement regarding the SARA legal listing process may begin by late 2020.

U.S.-Canada Collaboration

The 1985 Pacific Salmon Treaty set the long-term goals for the benefit of the salmon and the two countries. The Pacific Salmon Commission is the body formed by the governments of Canada and the United States to implement the Pacific Salmon Treaty and in 1999, the United States and Canada reached a comprehensive new agreement, which established two bilateral Restoration and Enhancement funds.

At a management scale, the Salish Sea Marine Survival Project is an example of a research project to improve our understanding about the weak survival rates of juvenile salmon. Managed by Long Live the Kings in Washington and the Pacific Salmon Foundation in British Columbia, the project brings together U.S. and Canadian experts from federal, state and provincial agencies, tribes and First Nations, and academic and nonprofit organizations. The project was started in 2012 to evaluate potential stressors on juvenile salmon survival and to help develop science-based solutions to guide improvements in salmon management. As of January 2019, over 90 studies were initiated by the project, with 25 published in peer-reviewed journals. A final synthesis report for the project is expected in 2020.

Actions in Canada

In 2005, the Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) released its Wild Salmon Policy to conserve wild salmon and their habitat. The policy aims to safeguard the genetic diversity of wild salmon populations, maintain habitat and ecosystem integrity, and manage fisheries for sustainable benefits.

In 2011, DFO launched a "license retirement" program to reduce harvests of Chinook salmon, including areas within the Canadian portion of the Salish Sea.

In 2019, DFO placed strict restrictions on Fraser River Chinook harvesting to allow more salmon to reach their spawning grounds. Commercial fishing was completely closed until the late summer season. Fishing for ceremonial purposes by First Nations and recreational fishing were allowed in only small amounts.

A natural landslide was discovered along the Fraser River in June 2019 that blocked the path of spawning Chinook and other salmon. A collaboration of DFO, the provincial government of British Columbia, and First Nations governments was formed quickly to plan and take immediate action to assist migrating salmon through the summer and fall of 2019. Work in the area is continuing in the winter of 2019-2020 to clear away fallen rock and improve the site for future migrating Chinook and other salmon species of the Fraser River.

Actions in the U.S.

In 2008, in agreement with NOAA's National Marine Fisheries Service, the Puget Sound Partnership (PSP) was designated to serve as Washington State’s regional salmon recovery organization for Puget Sound salmon species, excluding Hood Canal summer chum salmon. The Partnership implements the Puget Sound Salmon Recovery Plan to protect and restore habitat, raise public awareness, coordinate on habitat, hatchery, and harvest practices, and develop a monitoring and adaptive management strategy to help track and assess efforts to recover salmon in Puget Sound. The work is accomplished by working with the Puget Sound Salmon Recovery Council, which consists of local stakeholders and communities, tribes, businesses, and state and federal agencies. The PSP also co-manages the Puget Sound Acquisition and Restoration Fund with the Washington State Resource and Conservation Office (RCO), which supports salmon habitat restoration and protection.

In 2009, additional funds were authorized to lessen the impacts of harvest reductions, support the coded wire tag program (for salmon identification), improve analytical models, and implement individual stock-based management fisheries. The National Marine Fisheries Service, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the many tribes in Washington State work together to manage salmon fisheries. In addition to co-managing salmon harvest rates and hatchery influence, these entities work together to restore salmon habitat and monitor wild stock recovery after restoration efforts.

Related Projects

The following links exit the site

- Puget Sound National Estuary Program (NEP) Atlas - An interactive map showing conservation and restoration projects throughout the Puget Sound Basin.

- Estuary and Salmon Restoration Program - Providing funding and technical assistance to organizations working to restore shoreline and nearshore habitats critical to salmon and other species in Puget Sound. The program was established to advance projects using the scientific foundation developed by the Puget Sound Nearshore Ecosystem Restoration Project.

- Washington Shoreline Master Program Guidelines - The state rules that guide local governments in writing, adopting, and implementing local Shoreline Management Programs. They translate the broad policies of the state Shoreline Management Act into standards for regulating shoreline uses.

- State highways cross streams and rivers in thousands of places in Washington State, which can impede fish migration. The Washington State Department of Transport (WSDOT) has worked for nearly three decades to improve fish passage and reconnect streams to help keep our waterways healthy. WSDOT Fish Barrier Correction is a priority. Visit WSDOT's fish passage page to view the latest Fish Passage Annual Report and video. Also see how tribes, salmon recovery effort coalitions and local volunteers help to identify these problem culverts: Trekking the Backroads Counting Culverts for Salmon.

- Floodplains By Design (FbD) - an ambitious public-private partnership led by the Washington Department of Ecology, the Nature Conservancy, and the Puget Sound Partnership. FbD works to accelerate integrated efforts to reduce flood risks and restore habitat along Washington's major river corridors. Its goal is to improve the resiliency of floodplains in order to protect local communities and the health of the environment.

- British Columbia Salmon Restoration and Innovation Fund is a joint program of the Canadian federal government and the province of BC in place until March 2024, that will provide over $142 million CAD as funding for protection and restoration work for wild fish stocks (including salmon) and support BC’s fish and seafood industry. A list of funded projects, focused on innovation, infrastructure, and science partnerships is posted by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and includes: investing in research on climate change threats to Pacific salmonids; promoting environmental farm planning near salmon streams in the BC interior, and investigating infrastructure options for the Cowichan Lake – Cowichan River boundary to ensure river flows sustain salmon populations.

- The Watershed Watch Salmon Society is working to support the recovery of BC’s wild salmon in the lower Fraser River watershed. The organization has identified salmon habitat in BC potentially affected by flood control structures and is supporting a number of community projects to restore salmon habitat.

- Landowners and developers in BC can apply to certify their land as Salmon-Safe. The Fraser Basin Council and the Pacific Salmon Foundation launched the eco-certification program in 2011. The Fraser Basin Council has led the program since 2018. The certification recognizes and verifies when an urban or rural site uses practices that protect salmon habitat and support better water quality. The certification program is also available in the United States, as the Salmon-Safe certification was founded in Oregon but is now established all along the Pacific coast.

Learn More

Learn more about some of the work our partners are doing to protect Chinook salmon and their habitat.

- Pacific Salmon Commission

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada - Salmonid Enhancement Program

- Pacific Fishery Management Council

- NOAA Fisheries Salmon and Steelhead

- Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

- Washington Dept. of Fish and Wildlife "SalmonScape" Mapping System

- Puget Sound Partnership Vital Signs - Chinook Salmon

- Puget Sound Acquisition and Restoration Fund

- Long Live the Kings

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada – Species At Risk Act and Pacific Salmon

- Canada’s Species at Risk public registry – Chinook salmon

- Washington Recreation and Conservation Office - Lead entities for salmon recovery

Five Things You Can Do To Help

- Keep streams shaded. Trees and native vegetation along shorelines keep the water cool for fish and help stabilize the banks from erosion. Help protect these types of areas in your community and watch for stream restoration projects and opportunities.

- Keep litter and trash out of streams. Trash can pile up on logs, sticks and other debris and block water flow. Summer is the best time for in-stream cleanup to reduce impacts to key salmon life-cycle stages that typically occur in spring and fall.

- Help protect natural shorelines, wetlands and floodplains in your community. These habitats are extremely valuable to both salmon and people.

- Look for sustainably-harvested salmon at your local supermarket or favorite restaurant. When fishing, be aware of relevant local and national regulations that may restrict what species or amounts you can take.

- Get to know your local watershed group and volunteer to get involved.